Tell Me :

Talk

Photo is from a May 21, 2020 tweet.

[twitter.com]

Thanks, hadn't looked up their posting history as I thought it was a newly shared picture.

So it was just a month after the April 18th YCAGWYW stream with the air drums ;-)

--------------

IORR Links : Essential Studio Outtakes CDs : Audio - History of Rarest Outtakes : Audio

A beautiful photo - as is this one from Debbie Harry/Blondie

[twitter.com]

That Berry quote got right into my heart when I read it yesterday.

JumpingKentFlash

Heartfelt comments from Pete. Thanks for sharing MisterDDDD! I find myself numbed by Charlie's passing. Like a family member has suddenly died. After all, for many of us, Charlie and the boys have been in our lives since we were little kids back in the early to mid 60's. We grew up with these guys who were roughly 10 years older than me. They have been an important, constant part of our lives. That's just the way this has evolved, and who would have thought this is how it would be 58 years later?? Of course it was tragic when Brian died, but it didn't really come as a great surprise given his lifestyle at that time. But Charlie....I find that I am more sadly emotional today than yesterday. The gravity of this has really sunk in. We were/are lucky to have/had Charlie and the Stones for as long as this. Let's keep enjoying the music, and keep Charlie and his family in our thoughts and hearts.

ditto, keep 'em comming!

Poignant note from Bill. Let’s not forget Bill has lost a rhythm brother

Yeah, I agree, maybe once at the first show, but some sort of acknowledgement at the others.

Agree, yesterday was the shock, and just re-reading the news. Today, dealing with the loss. It's a beautiful day here in Massachusetts, and I'm in a dark room by myself staring at a computer. If someone didn't bring me food yesterday, i wouldn't have eaten. I think it's hitting us all really hard. I am sending a virtual hug to everyone that is hurting over this.

Talk about your favorite band.

For information about how to use this forum please check out forum help and policies.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

bye bye johnny

()

Date: August 25, 2021 18:44

Quote

gotdablouse

Is that possibly the last known picture of Charlie (apparently taken "just last year" so August 2020 ?) ? He didn't look very well sadly.

Photo is from a May 21, 2020 tweet.

[twitter.com]

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

MisterDDDD

()

Date: August 25, 2021 18:55

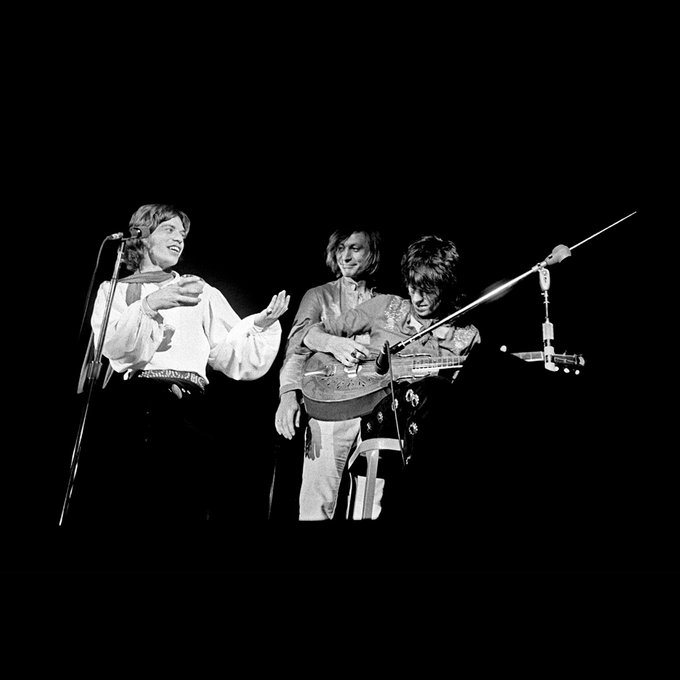

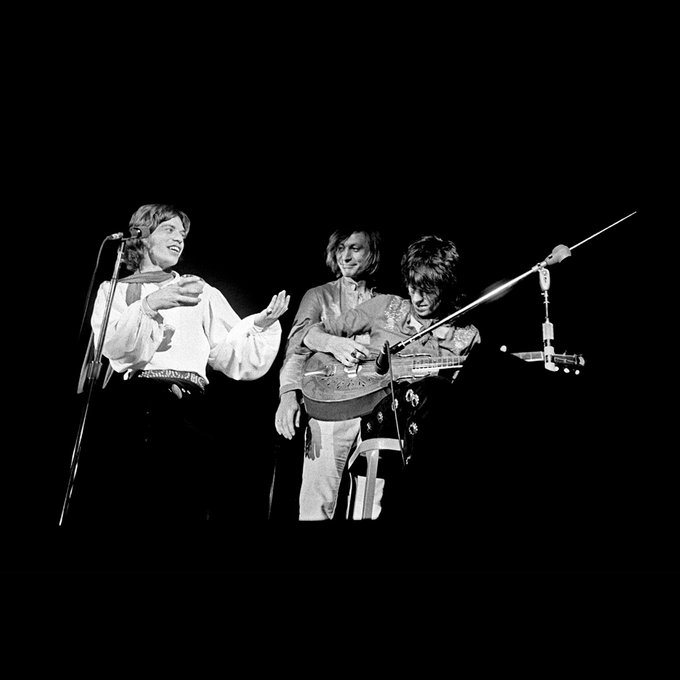

Ethan Russell

@ethan_russell

·

6m

More tribute to

@charliewatts

. I haven't shown this picture in yers (from 69 tour). Charlie has brought Mick a glass of water. I love the visibly good feeling between them and even Keith seems to be in on it..... RIP Charlie, a gentleman and a light.

[twitter.com]

@ethan_russell

·

6m

More tribute to

@charliewatts

. I haven't shown this picture in yers (from 69 tour). Charlie has brought Mick a glass of water. I love the visibly good feeling between them and even Keith seems to be in on it..... RIP Charlie, a gentleman and a light.

[twitter.com]

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

timmyj3

()

Date: August 25, 2021 18:58

Love this picture on this sad somber day.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

MisterDDDD

()

Date: August 25, 2021 18:59

Melissa Etheridge

@metheridge

·

We gave #CharlieWatts a rockin’ send off tonight

@ArtparkNY

#RIPCharlieWatts #RollingStones

@RollingStones

video

[twitter.com]

@metheridge

·

We gave #CharlieWatts a rockin’ send off tonight

@ArtparkNY

#RIPCharlieWatts #RollingStones

@RollingStones

video

[twitter.com]

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

gotdablouse

()

Date: August 25, 2021 19:00

Quote

bye bye johnnyQuote

gotdablouse

Is that possibly the last known picture of Charlie (apparently taken "just last year" so August 2020 ?) ? He didn't look very well sadly.

Photo is from a May 21, 2020 tweet.

[twitter.com]

Thanks, hadn't looked up their posting history as I thought it was a newly shared picture.

So it was just a month after the April 18th YCAGWYW stream with the air drums ;-)

--------------

IORR Links : Essential Studio Outtakes CDs : Audio - History of Rarest Outtakes : Audio

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

Lady Jayne

()

Date: August 25, 2021 19:01

Quote

MisterDDDD

Ethan Russell

@ethan_russell

·

6m

More tribute to

@charliewatts

. I haven't shown this picture in yers (from 69 tour). Charlie has brought Mick a glass of water. I love the visibly good feeling between them and even Keith seems to be in on it..... RIP Charlie, a gentleman and a light.

[twitter.com]

A beautiful photo - as is this one from Debbie Harry/Blondie

[twitter.com]

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

MisterDDDD

()

Date: August 25, 2021 19:06

Roger Daltrey, Pete Townshend Pay Their Respects to Charlie Watts

Roger Daltrey and Pete Townshend issued individual statements paying their respects to Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts.

Daltrey and Townshend’s statements were shared via The Who’s official website. Daltrey’s statement reads as follows:

“I would like to extend my deepest condolences to Charlie’s wife Shirley, the rest of his family and to the guys in the band.

He was always the perfect gentleman, as sharp in his manner of dress as he was on the drums.

Charlie was a truly great drummer, whose musical knowledge of drumming technique, from jazz to the blues, was, I’m sure, the heartbeat that made the Rolling Stones the best rock and roll band in the world.”

Townshend wrote a lengthy statement which reads:

“I only played with Charlie once, when he drummed for Ronnie Lane and me on our ‘Rough Mix’ album. We did two faultless live takes (no overdubs at all) of my song ‘My Baby Gives It Away’. His technique was obvious immediately, the hi-hat always slightly late, and the snare drumstick held in the flat of the left hand, underpowered to some extent, lazy-loose, super-cool. The swing on the track is explosive. I’ve never enjoyed playing with a drummer quite so much. Of course that brings up Keith Moon, who was so different to Charlie. At Keith’s funeral Charlie surprised me by openly weeping, and I remember wishing I could wear my heart on my sleeve like that. I was tightened up like a snare drum myself.

Charlie lived a quiet life in the English countryside. He had a London bolthole in St James’s for many years which I think he used mainly to visit his tailor and buy paintings. He is the exemplar of the perfect marriage, still married to his art-school girlfriend who he married secretly in 1964. I understand he lived a quiet and respectable life on the road as well. I know that like me he wasn’t mad on touring, but that wry smile of his – that hid a mischievous side to him that few us saw – could turn into the most beautiful wide-mouthed laugh at very little urging. I could make him smile simply by talking about growing up following my father Cliff’s post-war dance band. Charlie loved the ‘real’ music of that era.

I’ve said here that his playing on ‘My Baby Gives It Away’ was flawless. I have suddenly remembered that he had trouble with the clipped ending. On the second take he nailed it, but was so shocked he had managed it that he burst into laughter and fell off his stool. That was a Keith Moon stunt, ask any drummer what they most dread doing and they will probably reply that they never want to fall off their stool.”

[wror.com]

Roger Daltrey and Pete Townshend issued individual statements paying their respects to Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts.

Daltrey and Townshend’s statements were shared via The Who’s official website. Daltrey’s statement reads as follows:

“I would like to extend my deepest condolences to Charlie’s wife Shirley, the rest of his family and to the guys in the band.

He was always the perfect gentleman, as sharp in his manner of dress as he was on the drums.

Charlie was a truly great drummer, whose musical knowledge of drumming technique, from jazz to the blues, was, I’m sure, the heartbeat that made the Rolling Stones the best rock and roll band in the world.”

Townshend wrote a lengthy statement which reads:

“I only played with Charlie once, when he drummed for Ronnie Lane and me on our ‘Rough Mix’ album. We did two faultless live takes (no overdubs at all) of my song ‘My Baby Gives It Away’. His technique was obvious immediately, the hi-hat always slightly late, and the snare drumstick held in the flat of the left hand, underpowered to some extent, lazy-loose, super-cool. The swing on the track is explosive. I’ve never enjoyed playing with a drummer quite so much. Of course that brings up Keith Moon, who was so different to Charlie. At Keith’s funeral Charlie surprised me by openly weeping, and I remember wishing I could wear my heart on my sleeve like that. I was tightened up like a snare drum myself.

Charlie lived a quiet life in the English countryside. He had a London bolthole in St James’s for many years which I think he used mainly to visit his tailor and buy paintings. He is the exemplar of the perfect marriage, still married to his art-school girlfriend who he married secretly in 1964. I understand he lived a quiet and respectable life on the road as well. I know that like me he wasn’t mad on touring, but that wry smile of his – that hid a mischievous side to him that few us saw – could turn into the most beautiful wide-mouthed laugh at very little urging. I could make him smile simply by talking about growing up following my father Cliff’s post-war dance band. Charlie loved the ‘real’ music of that era.

I’ve said here that his playing on ‘My Baby Gives It Away’ was flawless. I have suddenly remembered that he had trouble with the clipped ending. On the second take he nailed it, but was so shocked he had managed it that he burst into laughter and fell off his stool. That was a Keith Moon stunt, ask any drummer what they most dread doing and they will probably reply that they never want to fall off their stool.”

[wror.com]

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

MisterDDDD

()

Date: August 25, 2021 19:15

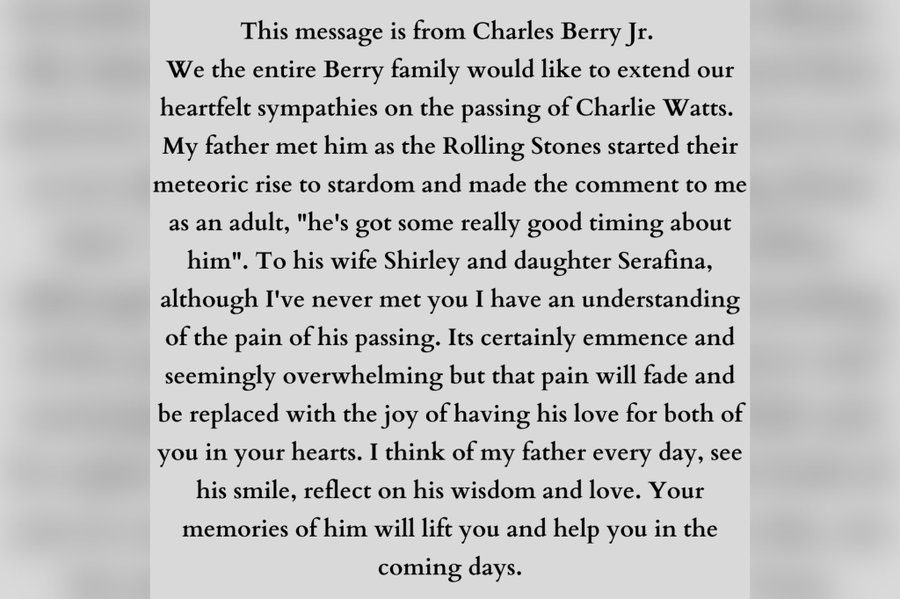

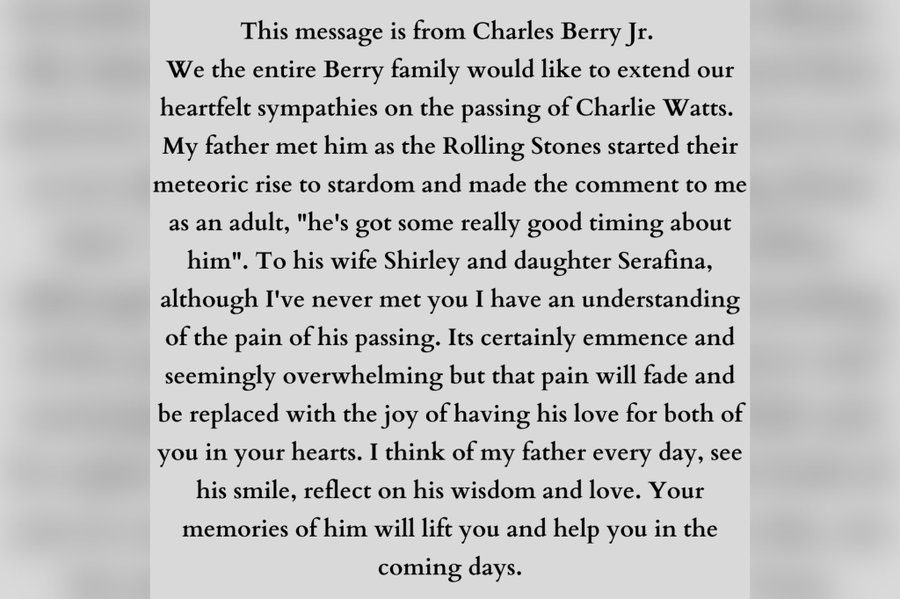

Chuck Berry

@ChuckBerry

·

1m

This message is from Charles Berry Jr. We the entire Berry family would like to extend our heartfelt sympathies on the passing of Charlie Watts...

[twitter.com]

@ChuckBerry

·

1m

This message is from Charles Berry Jr. We the entire Berry family would like to extend our heartfelt sympathies on the passing of Charlie Watts...

[twitter.com]

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

crawdaddy

()

Date: August 25, 2021 19:25

Tonight on UK BBC 2 there is The Rolling Stones at the BBC from 11.15pm - midnight.

Also for anyone in UK on BBC i player for next 30 days.

[www.bbc.co.uk]

Also for anyone in UK on BBC i player for next 30 days.

[www.bbc.co.uk]

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

JumpingKentFlash

()

Date: August 25, 2021 19:25

Quote

MisterDDDD

Chuck Berry

@ChuckBerry

·

1m

This message is from Charles Berry Jr. We the entire Berry family would like to extend our heartfelt sympathies on the passing of Charlie Watts...

[twitter.com]

That Berry quote got right into my heart when I read it yesterday.

JumpingKentFlash

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

filstan

()

Date: August 25, 2021 19:35

Quote

MisterDDDD

Roger Daltrey, Pete Townshend Pay Their Respects to Charlie Watts

Roger Daltrey and Pete Townshend issued individual statements paying their respects to Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts.

Daltrey and Townshend’s statements were shared via The Who’s official website. Daltrey’s statement reads as follows:

“I would like to extend my deepest condolences to Charlie’s wife Shirley, the rest of his family and to the guys in the band.

He was always the perfect gentleman, as sharp in his manner of dress as he was on the drums.

Charlie was a truly great drummer, whose musical knowledge of drumming technique, from jazz to the blues, was, I’m sure, the heartbeat that made the Rolling Stones the best rock and roll band in the world.”

Townshend wrote a lengthy statement which reads:

“I only played with Charlie once, when he drummed for Ronnie Lane and me on our ‘Rough Mix’ album. We did two faultless live takes (no overdubs at all) of my song ‘My Baby Gives It Away’. His technique was obvious immediately, the hi-hat always slightly late, and the snare drumstick held in the flat of the left hand, underpowered to some extent, lazy-loose, super-cool. The swing on the track is explosive. I’ve never enjoyed playing with a drummer quite so much. Of course that brings up Keith Moon, who was so different to Charlie. At Keith’s funeral Charlie surprised me by openly weeping, and I remember wishing I could wear my heart on my sleeve like that. I was tightened up like a snare drum myself.

Charlie lived a quiet life in the English countryside. He had a London bolthole in St James’s for many years which I think he used mainly to visit his tailor and buy paintings. He is the exemplar of the perfect marriage, still married to his art-school girlfriend who he married secretly in 1964. I understand he lived a quiet and respectable life on the road as well. I know that like me he wasn’t mad on touring, but that wry smile of his – that hid a mischievous side to him that few us saw – could turn into the most beautiful wide-mouthed laugh at very little urging. I could make him smile simply by talking about growing up following my father Cliff’s post-war dance band. Charlie loved the ‘real’ music of that era.

I’ve said here that his playing on ‘My Baby Gives It Away’ was flawless. I have suddenly remembered that he had trouble with the clipped ending. On the second take he nailed it, but was so shocked he had managed it that he burst into laughter and fell off his stool. That was a Keith Moon stunt, ask any drummer what they most dread doing and they will probably reply that they never want to fall off their stool.”

[wror.com]

Heartfelt comments from Pete. Thanks for sharing MisterDDDD! I find myself numbed by Charlie's passing. Like a family member has suddenly died. After all, for many of us, Charlie and the boys have been in our lives since we were little kids back in the early to mid 60's. We grew up with these guys who were roughly 10 years older than me. They have been an important, constant part of our lives. That's just the way this has evolved, and who would have thought this is how it would be 58 years later?? Of course it was tragic when Brian died, but it didn't really come as a great surprise given his lifestyle at that time. But Charlie....I find that I am more sadly emotional today than yesterday. The gravity of this has really sunk in. We were/are lucky to have/had Charlie and the Stones for as long as this. Let's keep enjoying the music, and keep Charlie and his family in our thoughts and hearts.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

MisterDDDD

()

Date: August 25, 2021 19:35

Charlie Watts Is a Jazz Drummer: The Lost ‘Rolling Stone’ Interview

In a previously unpublished interview from 2013, Watts goes deep into his favorite drummers, what the Stones do better than the Beatles, and outlasting almost every band.

In 2013, I interviewed the Rolling Stones for this magazine as the band prepared for the next leg of their 50th anniversary tour. I’d talked to Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, and Ron Wood before, but never Charlie Watts. I was excited by the prospect: For more years than I could count, I had wanted to be able to sit in a room and talk with him about jazz. I got to do that, but the section I wrote about him didn’t make the final story.

After I learned Watts would not be joining the Stones on tour this fall due to a health issue, I went back and reread the section, expanded it with some more passages from the interview. Now, on the heels of Watts’ death at age 80, I offer it in full. The piece raises a question: Are the Rolling Stones still the Rolling Stones without Charlie Watts? There can be no doubt that Mick Jagger and Keith Richards feel this demise immensely, since they have loved the man and have appreciated — for well over half a century — what he meant to their sound and history. They have carried indelible ghosts before, but Watts’ passing is a crushing loss. He was absolutely central to the Rolling Stones’ history, sound, and identity. — Mikal Gilmore

Charlie Watts is a jazz drummer. When he joined the Rolling Stones in 1963, in his early twenties, he had doubts about casting his lot with an outfit that — though a self-described blues ensemble — would quickly be identified as a teen-adored rock band, like the Beatles. He had drummed with bandleader Alexis Korner in London’s blues scene — which the Stones emerged from — but he always saw himself playing jazz. In 1965, he would publish an illustrated children’s book about bebop alto-saxophonist Charlie Parker, Ode to a High Flying Bird. (Much later, in 1992, he would record an album devoted to the late alto saxophonist, A Tribute to Charlie Parker With Strings.) Keith Richards has said he considers the Stones a jazz band — at least onstage — because of Watts.

It was Richards, Watts tells me, who taught him new ways to hear rock & roll: “While they were all going on about John Lee Hooker and all these other marvelous people [like] Muddy Waters, I’d be putting Charlie Parker and Sonny Rollins in. That’s what I was into when I joined the Rolling Stones, that’s what I used to listen to. Keith taught me to listen to Elvis Presley, because Elvis was someone I never bloody liked or listened to. Obviously, I’d heard ‘Hound Dog’ and all that, but to listen to him properly, Keith was the one who taught me.”

Watts also began listening to New Orleans musicians who played rock & roll and R&B as well as jazz. “Like Earl Phillips, Jimmy Reed’s drummer. Earl Phillips kind of played like a jazz drummer,” he says. “Another New Orleans drummer, Earl Palmer [who played with Dave Bartholomew, Fats Domino, Professor Longhair, and Little Richard, among others], always thought of himself as a jazz player — and, in fact, he was; he played for King Pleasure.”

Watts came to see how jazz and rock & roll emerged from similar backgrounds, sometimes played by the same players: “It’s quite a normal mixture in New Orleans for the drummers — somebody like Zigaboo [Joseph Modeliste, drummer for the Meters]. He could play bebop but also could play second-line rhythms. Ed Blackwell was a revolutionary drummer with Ornette Coleman’s quartet, and he was what we would call a jazz player, that’s what he did, that’s what he was. But he could play a New Orleans second line because he was from New Orleans.”

Watts has recorded 10 jazz albums on his own, in a wide variety of styles, starting in 1986 with Live at Fulham Town Hall, by the Charlie Watts Orchestra — an oversized orchestra that included seven trumpeters, four trombones, three altoists, six tenors, a baritonist, a clarinetist, two vibraphonists, piano, two basses, Jack Bruce on cello, and three drummers. It was abundantly arranged, and some of it — “Lester Leaps In,” with a massive tenor conflagration — was played at breakneck clips. In addition, he has issued recordings with a tentet, a quintet, plus a big band (which played versions of “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” and “Paint It, Black”); has recorded two Charlie Parker tributes; and has released two luxuriantly scored sets of American Songbook standards — Warm & Tender and Long Ago & Far Away, both featuring longtime Rolling Stones backing vocalist Bernard Fowler. On the vocal albums, Watts muted his rhythms into a faded heartbeat, guiding songs of longing and loss. His most adventurous work, though, was a sweeping tribute to jazz drummers, in collaboration with drummer Jim Keltner — who has played with Eric Clapton, Ry Cooder, Delaney & Bonnie, Bob Dylan, George Harrison, John Lennon, Ringo Starr, and Gábor Szabó, among numerous others.

When I meet Watts in a Beverly Hills hotel’s small, comfortable conference room, he is dressed in a fine gray suit, a couple shades darker than his swept back hair. He sits with his legs crossed, and his hands crossed at his wrists above them. I tell him I especially like the sprawling and ambitious Charlie Watts-Jim Keltner Project, on which the two played a series of nine tributes with such titles as “Kenny Clarke,” “Roy Haynes,” “Max Roach,” and “The Elvin Suite.” They didn’t attempt to emulate the drummers they were recognizing — though in the case of “Airto,” they fairly reconstructed the sound that the Brazilian percussionist evoked in Miles Davis’ 1970s ensembles.

For the most part, though, Watts and Keltner’s dedications were impressionistic constructions that caught something of the essence of the nine drummers they paid homage to, utilizing unusual instrumentation as well as occasional loops and electronics, plus West African-sounding rhythmic undertows. I tell Watts I especially liked the tracks named after Art Blakey and Tony Williams, and he seems surprised and grateful that an interviewer knows the album.

For me, Watts’ jazz recordings stand on their own yet also deepen an understanding of his place in the Rolling Stones. When you hear Watts drum with his stunning tentet on Watts at Scott’s, it’s as if all the beats withheld over the years from his work in an electric-blues and pop band have suddenly fallen into place. You can imagine superimposing one perspective over the other, and there you have it: A full picture of the history of drumming emerges in these recordings, as it developed in the blues-based formations of Blakey, Max Roach, and — a major touchstone for Watts — Elvin Jones, and finally informed the razor-edged swing that Watts instilled in the Rolling Stones, then winds up some place altogether different in his epic with Keltner.

Watts talks about seeing Tony Williams in the young drummer’s early years with Miles Davis. “He was so unlike anybody else,” he says. I mention that during an interview with Williams he once told me that the single influence who opened him to drumming so wide was Keith Moon. Watts’ eyes grow wide, and he leans his head rearward as if taken aback: “Blimey.”

When I thought about it, I say, it made sense. “Not to me,” says Watts. “Keith Moon, there was a character. Loved him. There’s only one of him. I miss him a lot. He was a very charming bloke, a lovely guy, really, but quite…”

Watts pauses to make a “whew” sound. “But he could be a difficult guy, really. Actually, there wasn’t only one of him. He was more like three people in one. He used to live here in Los Angeles for a while, in some of his madder days. God, I remember being here once with him when he tried to turn me on to chocolate ants; he was walking about with tins of chocolate ants. That’s what I mean. He was not your regular guy, in that way, but he was, in his heart, a nice guy. I always got on well with him.”

Watts shakes his head and smiles at the memory. “He was an amazing drummer with Pete [Townshend]. I don’t know if he was a very good drummer outside of Pete,” he adds, laughing. “A lot of guys, I don’t think, would have liked playing with him. He didn’t play real time or anything. He wasn’t funky or anything. He was a whole other thing. He was on top of everything, and maybe that’s what Tony liked, but you’d never think that Tony was like … I would have thought Roy Haynes was his big influence.

“Tony Williams was a lovely man, too, and he was writing some great stuff at the time he died. He was getting out, writing more than just playing. Brilliantly, he was writing brilliantly. He was very young when he joined Miles and became this iconic figure. I saw him when he was 18, I think, in London, the first time, when he had the black kit, and nobody played like that. Years later, when he died, I saw the brilliant Roy Haynes do his gig at Catalina’s, and I suddenly thought of Tony as an extension of Roy, which I never realized before. When Tony came to London in the Sixties with Miles, like I said before, he completely blew everybody away, because nobody played like that. They didn’t ride that way or do things like that. Then I saw his band Lifetime, of course, with Larry Young and John McLaughlin. I went with Mick Taylor to see that. It was fantastic. The three of them were incredible.”

Mainly what Watts talks about that afternoon is durability. I tell him that I’m not aware of any other drummer — at least not a well-known one — who has played with a musical unit for 50 years. For that matter, the only other band I can think of that ran that long was the Duke Ellington Band, from 1924 to 1974. Watts seems a little surprised as he pores over the thought of being the single longest-lasting band drummer in history. “Many guys have drummed 50 years,” he says, “but I guess it’s true, what you say. When we were going along through the years and people would say, ‘God, you’ve been going for 20 years,’ or something, my stock answer in those days was, ‘Yeah, but Duke Ellington has been going 40-something years.’ Of course, he never had the same band, really. He had a lot of the same guys in and out. The wonderful Sonny Greer was with him for, blimey, from when he was in his twenties; he must have been 30 years with him, easy, up to the 1950s. Then Ellington swapped a lot of drummers around. So, no, there haven’t been … I don’t know what that means, actually, 50 years with one band.”

It must mean that you really like it.

“Well, yeah. Also, I prefer bands to … I’m not Buddy Rich, I’ve never been a jazz musician that’s in a book that you ring up to do a gig. That would worry the life out of me, turning up and playing with people for the first time. I’ve never had that virtuosity. It takes about three or four gigs before I feel comfortable. Most of the drummers I love, really, are band guys, like Sonny. They’ve been in units for a while. It doesn’t happen so much nowadays. Roy Haynes, he’s been in so many great, great bands. Or the bands have been great with him in them, under great leaders — Lester Young, Charlie Parker, Gary Burton. Stan Getz had one of the great bands with him. There’s also a great record with Monk that he did, I think it’s one of the Five Spots. It’s amazing, really. There’s a great album he did with Coltrane called To the Beat of a Different Drum. Roy is an amazing guy who plays now as well as he’s ever played. If any young person asked me who they should follow in one’s life, I’d say Roy Haynes. He’s eternally young — there’s absolutely nothing wayward about him. He’s at an age where most guys are not even bothering with it, really. But you put your arm around him, he’s solid. He’s a fantastic man, and a very, very charming guy, beautiful man.

“When the Rolling Stones started, all those other bands were obviously going — they were big — and now we’ve gone past them in years, in longevity. This is nothing to do with fame and fortune or greatness. It’s just longevity, actually, and suddenly we’ve gone past them.”

I point out that probably nobody has drummed so hard, so relentlessly and fiercely as Watts over a lifetime. “That’s a drummer’s lot,” he says. “When you’d see Otis Redding, that band live, those tempos.… He was entertaining, doing it all, but he could stop during a sax solo or something. That drummer, though, was going the whole bloody time. It’s what you do. The drummer is the engine. It’s worse when you get tired and have a lot of the show still to do.

“There’s nothing worse than being out of breath or your hands are killing you, and you still have a quarter of the show to go. That’s the worst one. When you were young, you’d have a drink to get through that, but now I couldn’t do that. I like to be over-ready for things. That’s really one of the reasons why I started to play jazz — the love of it was another — but it was to do other things while we weren’t on the road, because we’d work for two years, and you’d be great at the end of it, and you wouldn’t work for another year or so. I like to do something to keep my hands going, really.”

There had been reports about tensions between Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. Were there any doubts about the 50th-anniversary tour happening?

“Not to me, but to many people there was a doubt. The two big offenders of that virtually lived together when they were kids, didn’t they? They lived down the road from each other. It comes from all that. They’re like brothers, arguing about the rent, and then if you get between it, forget it. They leave you high and dry. I think it’s part of being together for 50 years. Keith couldn’t say things in his book without knowing Mick that well. I haven’t read it, actually. I just heard things he’d said, and it’s what he felt.

“I always thought we should do something for the 50th year, which Bill Wyman informed me actually is this year — it wasn’t last year. I was very in favor of doing a show, or a few of them. It’s all right to do three numbers, but by the time you’ve rehearsed, paid for everybody, it’s like a juggernaut, our thing. It’s not just me and Keith turning up and having fun, although that really is what it is, but the whole thing of it turns into a production, so you generally have to do two or three shows to pay for thinking about getting it together.

“The shows in London and New York were good, and sort of spurred this on. I hope this is as comfortable as that was, because that was really comfortable to do. I like it when you can see the end of it. When you have an endless list of dates — 50 shows in America or something — you just look at it and go, ‘Oh, Christ.’ But it’s very tempting to carry on, once you’ve started that. As Keith would say, ‘Why don’t we do more?’ It’s logically the thing to do, because the start-up is the hard thing on your body. So obviously, nonstop is the best thing. We’ll see.”

Are the Rolling Stones the best at being the Rolling Stones when they’re on tour or onstage?

“Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah, we are a live band. We always have been, even in the early days. The Beatles were fabulous in a studio, getting their songs together, but we were much better at entertaining — we were more raucous. I think we’re a better live band than a lot. For your ego, there’s nothing nicer than driving down Santa Monica and hearing yourself on the radio, especially if it’s a new record. But the real fun is on the stage.

“That’s why I like jazz and why I prefer playing in clubs, because it’s more immediate. It’s just what I like. And I think everybody does, probably apart from Mick, who’s more about songwriting, that sort of thing. I’m sure Keith prefers playing live to the other stuff.” Watts laughs. “People would look at us and hear the music and think, ‘God, why do you bother to rehearse for that?’ But we always do, and we always have.”

Every night, I offer, it seems like there’s breathing room, there’s a chance for something a little different.

“A lot of that comes from Keith, really. Keith’s very much like playing with a jazz guy, very loose. He can go anywhere, and if you follow him and it’s right, it’s something special, which is kind of what happens with jazz in its moments, really. He’s very much like that. It’s very easy to play with him. You can go anywhere, really, sometimes. Roy Haynes told me you had to be quick with Bird [Charlie Parker], because he was so quick thinking, his little inflections and that. Keith’s kind of like that. I don’t mean Keith’s like Charlie Parker, but it’s the same feeling. It can go somewhere quick, and if you go with it where he thinks it should go, it’s a lot of fun. That’s why it’s loose. Sometimes we don’t go with it, and it falls apart.

Is “going with it” more difficult on large stages in arenas?

“You can hear better, obviously, in a smaller room, except now the stage equipment is so advanced. In the early days, Keith used to have his Vox amplifier on a chair, tilted up so I could hear him. He still does, actually — he has it right by my hi-hat, so I can hear him. In the early days, when it was what I call the Beatle period, which was all screaming girls, you couldn’t hear a bloody thing, but I had to really hear him to know where the song is, because in those days, you didn’t have very good PA. I couldn’t hear what Mick was singing, really. Now, it’s quite sophisticated, but also it’s incredibly loud. When a band like ours goes into a small club, it carries half of that with it, and it’s miles too loud for me in a club. We never used to be like that. It’s very difficult to suddenly jump from that huge stage down to that. It’s pretty hard.”

Keith Richards tells me, more than once, that Watts is essentially the reason that he still plays with Mick Jagger, and the reason the Rolling Stones endure so well and renew so effectively. Jagger, too, has said he can’t imagine the band continuing without Watts. The Rolling Stones could survive the loss of guitarists Brian Jones and Mick Taylor, and the departure of bassist Bill Wyman. They can withstand years of a world’s distance apart from one another. But they can’t imagine truly being the Rolling Stones without Charlie Watts. Watts is similar-minded: “They are the only people I want to play rock & roll with.”

Much of this is to say that when the Rolling Stones play music together, when they walk onstage together, they are an interesting coalition of history, musicianship, personality, pain, loss, joy, daring, change, and — most important — roughhewn fellowship.

By this time, the longevity of the Rolling Stones has become as distinguishing a characteristic of the band’s history as their blues-indebtedness and all the notoriety and rebelliousness that put them on the map in the first place. That longevity, of course, has taken its toll — at moments their union seemed strained beyond any hope of repair. Yet they know there’s an alchemy at work between them, a collective mystery that is beyond their individual talents or reputations.

Past that, none of the three original members — Watts, Jagger, Richards — is at ease offering insight into why their legend and appeal survive so potently, but they realize that it endures when they are together, especially in the presence of an audience.

“We’re very, very fortunate,” says Watts. “I’ve always felt that folks have liked this combination of people. Mick, Keith, Brian, and Bill: People turned up to see them. First it was 100 attending, then it was 200, then it’s a lot. People love looking at Mick Jagger and watching what Keith’s doing. I don’t know why, but they do. I mean, I do know, I know how good Keith is, and I know Mick is the best frontman going now that James Brown and Michael Jackson have gone. Being out there, he’s the best. He takes it deadly seriously, as well; he keeps himself together. He looks great — everything you could want. You wouldn’t expect them to turn up to see me — it’s, like, 200 people — but the Rolling Stones say they’re doing something, and we get more people standing outside, listening to our rehearsals, than I do in a club listening to me do a set. It’s something that I’ve got no idea why.”

[www.rollingstone.com]

In a previously unpublished interview from 2013, Watts goes deep into his favorite drummers, what the Stones do better than the Beatles, and outlasting almost every band.

In 2013, I interviewed the Rolling Stones for this magazine as the band prepared for the next leg of their 50th anniversary tour. I’d talked to Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, and Ron Wood before, but never Charlie Watts. I was excited by the prospect: For more years than I could count, I had wanted to be able to sit in a room and talk with him about jazz. I got to do that, but the section I wrote about him didn’t make the final story.

After I learned Watts would not be joining the Stones on tour this fall due to a health issue, I went back and reread the section, expanded it with some more passages from the interview. Now, on the heels of Watts’ death at age 80, I offer it in full. The piece raises a question: Are the Rolling Stones still the Rolling Stones without Charlie Watts? There can be no doubt that Mick Jagger and Keith Richards feel this demise immensely, since they have loved the man and have appreciated — for well over half a century — what he meant to their sound and history. They have carried indelible ghosts before, but Watts’ passing is a crushing loss. He was absolutely central to the Rolling Stones’ history, sound, and identity. — Mikal Gilmore

Charlie Watts is a jazz drummer. When he joined the Rolling Stones in 1963, in his early twenties, he had doubts about casting his lot with an outfit that — though a self-described blues ensemble — would quickly be identified as a teen-adored rock band, like the Beatles. He had drummed with bandleader Alexis Korner in London’s blues scene — which the Stones emerged from — but he always saw himself playing jazz. In 1965, he would publish an illustrated children’s book about bebop alto-saxophonist Charlie Parker, Ode to a High Flying Bird. (Much later, in 1992, he would record an album devoted to the late alto saxophonist, A Tribute to Charlie Parker With Strings.) Keith Richards has said he considers the Stones a jazz band — at least onstage — because of Watts.

It was Richards, Watts tells me, who taught him new ways to hear rock & roll: “While they were all going on about John Lee Hooker and all these other marvelous people [like] Muddy Waters, I’d be putting Charlie Parker and Sonny Rollins in. That’s what I was into when I joined the Rolling Stones, that’s what I used to listen to. Keith taught me to listen to Elvis Presley, because Elvis was someone I never bloody liked or listened to. Obviously, I’d heard ‘Hound Dog’ and all that, but to listen to him properly, Keith was the one who taught me.”

Watts also began listening to New Orleans musicians who played rock & roll and R&B as well as jazz. “Like Earl Phillips, Jimmy Reed’s drummer. Earl Phillips kind of played like a jazz drummer,” he says. “Another New Orleans drummer, Earl Palmer [who played with Dave Bartholomew, Fats Domino, Professor Longhair, and Little Richard, among others], always thought of himself as a jazz player — and, in fact, he was; he played for King Pleasure.”

Watts came to see how jazz and rock & roll emerged from similar backgrounds, sometimes played by the same players: “It’s quite a normal mixture in New Orleans for the drummers — somebody like Zigaboo [Joseph Modeliste, drummer for the Meters]. He could play bebop but also could play second-line rhythms. Ed Blackwell was a revolutionary drummer with Ornette Coleman’s quartet, and he was what we would call a jazz player, that’s what he did, that’s what he was. But he could play a New Orleans second line because he was from New Orleans.”

Watts has recorded 10 jazz albums on his own, in a wide variety of styles, starting in 1986 with Live at Fulham Town Hall, by the Charlie Watts Orchestra — an oversized orchestra that included seven trumpeters, four trombones, three altoists, six tenors, a baritonist, a clarinetist, two vibraphonists, piano, two basses, Jack Bruce on cello, and three drummers. It was abundantly arranged, and some of it — “Lester Leaps In,” with a massive tenor conflagration — was played at breakneck clips. In addition, he has issued recordings with a tentet, a quintet, plus a big band (which played versions of “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” and “Paint It, Black”); has recorded two Charlie Parker tributes; and has released two luxuriantly scored sets of American Songbook standards — Warm & Tender and Long Ago & Far Away, both featuring longtime Rolling Stones backing vocalist Bernard Fowler. On the vocal albums, Watts muted his rhythms into a faded heartbeat, guiding songs of longing and loss. His most adventurous work, though, was a sweeping tribute to jazz drummers, in collaboration with drummer Jim Keltner — who has played with Eric Clapton, Ry Cooder, Delaney & Bonnie, Bob Dylan, George Harrison, John Lennon, Ringo Starr, and Gábor Szabó, among numerous others.

When I meet Watts in a Beverly Hills hotel’s small, comfortable conference room, he is dressed in a fine gray suit, a couple shades darker than his swept back hair. He sits with his legs crossed, and his hands crossed at his wrists above them. I tell him I especially like the sprawling and ambitious Charlie Watts-Jim Keltner Project, on which the two played a series of nine tributes with such titles as “Kenny Clarke,” “Roy Haynes,” “Max Roach,” and “The Elvin Suite.” They didn’t attempt to emulate the drummers they were recognizing — though in the case of “Airto,” they fairly reconstructed the sound that the Brazilian percussionist evoked in Miles Davis’ 1970s ensembles.

For the most part, though, Watts and Keltner’s dedications were impressionistic constructions that caught something of the essence of the nine drummers they paid homage to, utilizing unusual instrumentation as well as occasional loops and electronics, plus West African-sounding rhythmic undertows. I tell Watts I especially liked the tracks named after Art Blakey and Tony Williams, and he seems surprised and grateful that an interviewer knows the album.

For me, Watts’ jazz recordings stand on their own yet also deepen an understanding of his place in the Rolling Stones. When you hear Watts drum with his stunning tentet on Watts at Scott’s, it’s as if all the beats withheld over the years from his work in an electric-blues and pop band have suddenly fallen into place. You can imagine superimposing one perspective over the other, and there you have it: A full picture of the history of drumming emerges in these recordings, as it developed in the blues-based formations of Blakey, Max Roach, and — a major touchstone for Watts — Elvin Jones, and finally informed the razor-edged swing that Watts instilled in the Rolling Stones, then winds up some place altogether different in his epic with Keltner.

Watts talks about seeing Tony Williams in the young drummer’s early years with Miles Davis. “He was so unlike anybody else,” he says. I mention that during an interview with Williams he once told me that the single influence who opened him to drumming so wide was Keith Moon. Watts’ eyes grow wide, and he leans his head rearward as if taken aback: “Blimey.”

When I thought about it, I say, it made sense. “Not to me,” says Watts. “Keith Moon, there was a character. Loved him. There’s only one of him. I miss him a lot. He was a very charming bloke, a lovely guy, really, but quite…”

Watts pauses to make a “whew” sound. “But he could be a difficult guy, really. Actually, there wasn’t only one of him. He was more like three people in one. He used to live here in Los Angeles for a while, in some of his madder days. God, I remember being here once with him when he tried to turn me on to chocolate ants; he was walking about with tins of chocolate ants. That’s what I mean. He was not your regular guy, in that way, but he was, in his heart, a nice guy. I always got on well with him.”

Watts shakes his head and smiles at the memory. “He was an amazing drummer with Pete [Townshend]. I don’t know if he was a very good drummer outside of Pete,” he adds, laughing. “A lot of guys, I don’t think, would have liked playing with him. He didn’t play real time or anything. He wasn’t funky or anything. He was a whole other thing. He was on top of everything, and maybe that’s what Tony liked, but you’d never think that Tony was like … I would have thought Roy Haynes was his big influence.

“Tony Williams was a lovely man, too, and he was writing some great stuff at the time he died. He was getting out, writing more than just playing. Brilliantly, he was writing brilliantly. He was very young when he joined Miles and became this iconic figure. I saw him when he was 18, I think, in London, the first time, when he had the black kit, and nobody played like that. Years later, when he died, I saw the brilliant Roy Haynes do his gig at Catalina’s, and I suddenly thought of Tony as an extension of Roy, which I never realized before. When Tony came to London in the Sixties with Miles, like I said before, he completely blew everybody away, because nobody played like that. They didn’t ride that way or do things like that. Then I saw his band Lifetime, of course, with Larry Young and John McLaughlin. I went with Mick Taylor to see that. It was fantastic. The three of them were incredible.”

Mainly what Watts talks about that afternoon is durability. I tell him that I’m not aware of any other drummer — at least not a well-known one — who has played with a musical unit for 50 years. For that matter, the only other band I can think of that ran that long was the Duke Ellington Band, from 1924 to 1974. Watts seems a little surprised as he pores over the thought of being the single longest-lasting band drummer in history. “Many guys have drummed 50 years,” he says, “but I guess it’s true, what you say. When we were going along through the years and people would say, ‘God, you’ve been going for 20 years,’ or something, my stock answer in those days was, ‘Yeah, but Duke Ellington has been going 40-something years.’ Of course, he never had the same band, really. He had a lot of the same guys in and out. The wonderful Sonny Greer was with him for, blimey, from when he was in his twenties; he must have been 30 years with him, easy, up to the 1950s. Then Ellington swapped a lot of drummers around. So, no, there haven’t been … I don’t know what that means, actually, 50 years with one band.”

It must mean that you really like it.

“Well, yeah. Also, I prefer bands to … I’m not Buddy Rich, I’ve never been a jazz musician that’s in a book that you ring up to do a gig. That would worry the life out of me, turning up and playing with people for the first time. I’ve never had that virtuosity. It takes about three or four gigs before I feel comfortable. Most of the drummers I love, really, are band guys, like Sonny. They’ve been in units for a while. It doesn’t happen so much nowadays. Roy Haynes, he’s been in so many great, great bands. Or the bands have been great with him in them, under great leaders — Lester Young, Charlie Parker, Gary Burton. Stan Getz had one of the great bands with him. There’s also a great record with Monk that he did, I think it’s one of the Five Spots. It’s amazing, really. There’s a great album he did with Coltrane called To the Beat of a Different Drum. Roy is an amazing guy who plays now as well as he’s ever played. If any young person asked me who they should follow in one’s life, I’d say Roy Haynes. He’s eternally young — there’s absolutely nothing wayward about him. He’s at an age where most guys are not even bothering with it, really. But you put your arm around him, he’s solid. He’s a fantastic man, and a very, very charming guy, beautiful man.

“When the Rolling Stones started, all those other bands were obviously going — they were big — and now we’ve gone past them in years, in longevity. This is nothing to do with fame and fortune or greatness. It’s just longevity, actually, and suddenly we’ve gone past them.”

I point out that probably nobody has drummed so hard, so relentlessly and fiercely as Watts over a lifetime. “That’s a drummer’s lot,” he says. “When you’d see Otis Redding, that band live, those tempos.… He was entertaining, doing it all, but he could stop during a sax solo or something. That drummer, though, was going the whole bloody time. It’s what you do. The drummer is the engine. It’s worse when you get tired and have a lot of the show still to do.

“There’s nothing worse than being out of breath or your hands are killing you, and you still have a quarter of the show to go. That’s the worst one. When you were young, you’d have a drink to get through that, but now I couldn’t do that. I like to be over-ready for things. That’s really one of the reasons why I started to play jazz — the love of it was another — but it was to do other things while we weren’t on the road, because we’d work for two years, and you’d be great at the end of it, and you wouldn’t work for another year or so. I like to do something to keep my hands going, really.”

There had been reports about tensions between Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. Were there any doubts about the 50th-anniversary tour happening?

“Not to me, but to many people there was a doubt. The two big offenders of that virtually lived together when they were kids, didn’t they? They lived down the road from each other. It comes from all that. They’re like brothers, arguing about the rent, and then if you get between it, forget it. They leave you high and dry. I think it’s part of being together for 50 years. Keith couldn’t say things in his book without knowing Mick that well. I haven’t read it, actually. I just heard things he’d said, and it’s what he felt.

“I always thought we should do something for the 50th year, which Bill Wyman informed me actually is this year — it wasn’t last year. I was very in favor of doing a show, or a few of them. It’s all right to do three numbers, but by the time you’ve rehearsed, paid for everybody, it’s like a juggernaut, our thing. It’s not just me and Keith turning up and having fun, although that really is what it is, but the whole thing of it turns into a production, so you generally have to do two or three shows to pay for thinking about getting it together.

“The shows in London and New York were good, and sort of spurred this on. I hope this is as comfortable as that was, because that was really comfortable to do. I like it when you can see the end of it. When you have an endless list of dates — 50 shows in America or something — you just look at it and go, ‘Oh, Christ.’ But it’s very tempting to carry on, once you’ve started that. As Keith would say, ‘Why don’t we do more?’ It’s logically the thing to do, because the start-up is the hard thing on your body. So obviously, nonstop is the best thing. We’ll see.”

Are the Rolling Stones the best at being the Rolling Stones when they’re on tour or onstage?

“Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah, we are a live band. We always have been, even in the early days. The Beatles were fabulous in a studio, getting their songs together, but we were much better at entertaining — we were more raucous. I think we’re a better live band than a lot. For your ego, there’s nothing nicer than driving down Santa Monica and hearing yourself on the radio, especially if it’s a new record. But the real fun is on the stage.

“That’s why I like jazz and why I prefer playing in clubs, because it’s more immediate. It’s just what I like. And I think everybody does, probably apart from Mick, who’s more about songwriting, that sort of thing. I’m sure Keith prefers playing live to the other stuff.” Watts laughs. “People would look at us and hear the music and think, ‘God, why do you bother to rehearse for that?’ But we always do, and we always have.”

Every night, I offer, it seems like there’s breathing room, there’s a chance for something a little different.

“A lot of that comes from Keith, really. Keith’s very much like playing with a jazz guy, very loose. He can go anywhere, and if you follow him and it’s right, it’s something special, which is kind of what happens with jazz in its moments, really. He’s very much like that. It’s very easy to play with him. You can go anywhere, really, sometimes. Roy Haynes told me you had to be quick with Bird [Charlie Parker], because he was so quick thinking, his little inflections and that. Keith’s kind of like that. I don’t mean Keith’s like Charlie Parker, but it’s the same feeling. It can go somewhere quick, and if you go with it where he thinks it should go, it’s a lot of fun. That’s why it’s loose. Sometimes we don’t go with it, and it falls apart.

Is “going with it” more difficult on large stages in arenas?

“You can hear better, obviously, in a smaller room, except now the stage equipment is so advanced. In the early days, Keith used to have his Vox amplifier on a chair, tilted up so I could hear him. He still does, actually — he has it right by my hi-hat, so I can hear him. In the early days, when it was what I call the Beatle period, which was all screaming girls, you couldn’t hear a bloody thing, but I had to really hear him to know where the song is, because in those days, you didn’t have very good PA. I couldn’t hear what Mick was singing, really. Now, it’s quite sophisticated, but also it’s incredibly loud. When a band like ours goes into a small club, it carries half of that with it, and it’s miles too loud for me in a club. We never used to be like that. It’s very difficult to suddenly jump from that huge stage down to that. It’s pretty hard.”

Keith Richards tells me, more than once, that Watts is essentially the reason that he still plays with Mick Jagger, and the reason the Rolling Stones endure so well and renew so effectively. Jagger, too, has said he can’t imagine the band continuing without Watts. The Rolling Stones could survive the loss of guitarists Brian Jones and Mick Taylor, and the departure of bassist Bill Wyman. They can withstand years of a world’s distance apart from one another. But they can’t imagine truly being the Rolling Stones without Charlie Watts. Watts is similar-minded: “They are the only people I want to play rock & roll with.”

Much of this is to say that when the Rolling Stones play music together, when they walk onstage together, they are an interesting coalition of history, musicianship, personality, pain, loss, joy, daring, change, and — most important — roughhewn fellowship.

By this time, the longevity of the Rolling Stones has become as distinguishing a characteristic of the band’s history as their blues-indebtedness and all the notoriety and rebelliousness that put them on the map in the first place. That longevity, of course, has taken its toll — at moments their union seemed strained beyond any hope of repair. Yet they know there’s an alchemy at work between them, a collective mystery that is beyond their individual talents or reputations.

Past that, none of the three original members — Watts, Jagger, Richards — is at ease offering insight into why their legend and appeal survive so potently, but they realize that it endures when they are together, especially in the presence of an audience.

“We’re very, very fortunate,” says Watts. “I’ve always felt that folks have liked this combination of people. Mick, Keith, Brian, and Bill: People turned up to see them. First it was 100 attending, then it was 200, then it’s a lot. People love looking at Mick Jagger and watching what Keith’s doing. I don’t know why, but they do. I mean, I do know, I know how good Keith is, and I know Mick is the best frontman going now that James Brown and Michael Jackson have gone. Being out there, he’s the best. He takes it deadly seriously, as well; he keeps himself together. He looks great — everything you could want. You wouldn’t expect them to turn up to see me — it’s, like, 200 people — but the Rolling Stones say they’re doing something, and we get more people standing outside, listening to our rehearsals, than I do in a club listening to me do a set. It’s something that I’ve got no idea why.”

[www.rollingstone.com]

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

MisterDDDD

()

Date: August 25, 2021 19:40

U2

@U2

·

20s

“You make a grown man cry…” RIP Charlie Watts (2/6/41-24/8/21)

Effortless elegance

The rock of The Rolling Stones

Bono, Edge, Adam and Larry

[twitter.com]

@U2

·

20s

“You make a grown man cry…” RIP Charlie Watts (2/6/41-24/8/21)

Effortless elegance

The rock of The Rolling Stones

Bono, Edge, Adam and Larry

[twitter.com]

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

crawdaddy

()

Date: August 25, 2021 19:48

Lovely interview with Charlie.

Thanks for posting MisterDDDD .

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2021-08-25 19:51 by crawdaddy.

Thanks for posting MisterDDDD .

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2021-08-25 19:51 by crawdaddy.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

filstan

()

Date: August 25, 2021 20:06

Quote

crawdaddy

Lovely interview with Charlie.

Thanks for posting MisterDDDD .

ditto, keep 'em comming!

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

Rollin92

()

Date: August 25, 2021 20:17

Poignant note from Bill. Let’s not forget Bill has lost a rhythm brother

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

kovach

()

Date: August 25, 2021 20:32

Quote

24FPSQuote

kovachQuote

GJB

The whole Rolling Stones website redirects to this:

[rollingstones.com]

I think that it a fitting tribute - right now, nothing else matters, the tour, the future, the album, the re-issues...

Let's just have this time to raise a glass to the Salt of the Band...

My favourite memories include:

- Coventry (2018) everyone singing Happy Birthday to Charlie

- Paris (2017) Charlie laughing as Mick takes drumstick and crashes his cymbals while playing Street Fighting Man

- London Rehearsals (seeing the band up close - the last time I have seen the Stones, and what a special time)

I was thinking about this last night while trying to sleep...hoping they properly address Charlie and don't just carry on with a mention like The Who did with Entwistle and ZZ Top did with Dusty. Maybe Mick or all 3 entering a dark stage and reading a short eulogy like Mick did for Brian at Hyde Park in 69 and starting the show off low-key with an acoustic melody of Salt of the Earth and Shine a Light or something before the standard video start to the main show. Maybe dedicate every show of this tour to Charlie. If they're going to carry on that might be the most fitting way.

I can't see Mick doing that. Maybe once.

Yeah, I agree, maybe once at the first show, but some sort of acknowledgement at the others.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

wesley

()

Date: August 25, 2021 20:34

Devastated and sad.

At the same time so pleased to have seen the Stones seven times. Charlie was the heartbeat of the live Stones.

At the same time so pleased to have seen the Stones seven times. Charlie was the heartbeat of the live Stones.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

Ellipooh

()

Date: August 25, 2021 20:47

Loved that "lost" interview Mister DDDD, thanks for posting it. Well worth the time to read it.

***Can't you hear me knocking?***

***Can't you hear me knocking?***

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

JN99

()

Date: August 25, 2021 20:50

Yesterday's shock has settled in with today's immense sadness. I am surprised at the depth of it. Though I always knew it would be a very sad day when one of these men passed, I had no idea just how hard it would hit me. It just hurts and I feel a void I've scarcely known. I still can't believe it.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

bye bye johnny

()

Date: August 25, 2021 20:55

There Will Never Be Another Drummer Like Charlie Watts

The Rolling Stones owe their greatest music to this greatest of drummers.

By Jack Hamilton

Aug 25, 202112:27 PM

Charlie Watts performing on tour in July 2019. Suzanne Cordeiro/Getty Images

[slate.com]

The Rolling Stones owe their greatest music to this greatest of drummers.

By Jack Hamilton

Aug 25, 202112:27 PM

Charlie Watts performing on tour in July 2019. Suzanne Cordeiro/Getty Images

[slate.com]

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

MisterDDDD

()

Date: August 25, 2021 20:59

Bill Clinton

@BillClinton

·

8m

Saddened by the passing of Charlie Watts, one of the greatest drummers of all time and a really good man. Thanks for the music and the memories. My thoughts are with his family and his brothers in the

@RollingStones

[twitter.com]

@BillClinton

·

8m

Saddened by the passing of Charlie Watts, one of the greatest drummers of all time and a really good man. Thanks for the music and the memories. My thoughts are with his family and his brothers in the

@RollingStones

[twitter.com]

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

ribbelchips

()

Date: August 25, 2021 21:03

Any news on his funeral yet?

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

DGA35

()

Date: August 25, 2021 21:03

Alex Van Halen, who isn't on social media, sent a note to the Van Halen News Desk website to post: Dear Charlie. Godspeed.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

MisterDDDD

()

Date: August 25, 2021 21:06

Remembering Charlie Watts, And Looking Back At The Rolling Stones’ Deep Ties To Chicago And The Blues

By CBS 2 Chicago StaffAugust 24, 2021 at 11:09 pm

CHICAGO (CBS Chicago/CBS News) — Charlie Watts, the drummer whose beat kept The Rolling Stones alive for six decades, has died.

Publicist Bernard Doherty said Tuesday that Watts “passed away peacefully in a London hospital earlier today surrounded by his family.” Watts was 80.

Bandmates Mick Jagger and Keith Richards each left tributes to Watts on Tuesday, using images rather than words.

Watts had announced earlier this month he would not tour with the Stones in 2021 because of an undefined health issue. When Watts turned 80 in June, Jagger posted a birthday message and video montage of the drummer on Twitter.

Watts was a lifelong jazz lover, preferring Miles Davis to Elvis Presley. But Keith Richards used the records of Muddy Waters and other Chicago blues icons to give the Stones their name and much of their sound – and to convert Watts into a rock and roll drummer.

The Rolling Stones, of course, have played in Chicago several dozen times. But their first visit to Chicago was not to play a concert, but to record at Chess Studios.

“They came here on their first tour of America and they recorded in Chess Studios. Chess Records was so seminal and so important to them that it was a dream come true when the first time they were in America they got to record at Chess,” said Ileen Gallagher, the curator of the touring “Exhibitionism” exhibit of Rolling Stones memorabilia that made a stop at Navy Pier in 2017.

“Chicago is the home of the blues and the Stones are a band because of the blues, so the fact that it’s here, it’s the way it should be,” said Chicago photographer Paul Natkin told WBBM Newsradio in a 2017 interview about the exhibit at Navy Pier.

Chess Records was founded by brothers Leonard and Phil Chess in 1950. It is renowned as the recording home of Father of Rock and Roll Chuck Berry – who commuted to Chicago from St. Louis to record all his best-known hits – as well as R&B pioneer Bo Diddley, and blues icons Little Walter, Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon, and of course, Muddy Waters.

The Rolling Stones held a session at Chess Studios in June 1964. In his memoir, “Life,” guitarist Richards wrote that the band recorded 14 tracks in two days. The recordings included Bobby Womack’s “It’s All Over Now” – which became a hit for the Stones – as well as some blues and Berry covers, and an instrumental blues jam honoring the Near South Side street address of the Chess Studios, “2120 South Michigan Avenue.

Richards also wrote that they encountered Muddy Waters on a ladder painting the ceiling at Chess. Seventeen years later in 1981, Waters would join them onstage at the old Checkerboard Lounge, at 423 E. 43rd St. in Bronzeville, for a concert that was memorialized on the album “Live at the Checkerboard Lounge.”

The Rolling Stones’ first Chicago show was at the Arie Crown Theater at McCormick Place in the fall of 1964, and they have played many dozens of shows since. They’ve played at long-gone venues such as the International Amphitheatre and the Chicago Stadium, and extant venues from Soldier Field to the United Center and what is now Guaranteed Rate Field – as well as the old Double Door in Wicker Park and the Aragon Ballroom in Uptown.

They most recently played to a sold-out crowd at Soldier Field in 2019. And as Lin Brehmer of WXRT radio recalled, Watts was as great as ever.

“And there was Charlie, what – 78 years old? Pounding the skins,” Brehmer said, “and he was phenomenal.”

Brehmer added: “One of the things that’s driving me crazy today is people saying, ‘Oh, what an underrated drummer.’ And if you paid any attention to the Rolling Stones, nobody underrated Charlie Watts.”

[chicago.cbslocal.com]

By CBS 2 Chicago StaffAugust 24, 2021 at 11:09 pm

CHICAGO (CBS Chicago/CBS News) — Charlie Watts, the drummer whose beat kept The Rolling Stones alive for six decades, has died.

Publicist Bernard Doherty said Tuesday that Watts “passed away peacefully in a London hospital earlier today surrounded by his family.” Watts was 80.

Bandmates Mick Jagger and Keith Richards each left tributes to Watts on Tuesday, using images rather than words.

Watts had announced earlier this month he would not tour with the Stones in 2021 because of an undefined health issue. When Watts turned 80 in June, Jagger posted a birthday message and video montage of the drummer on Twitter.

Watts was a lifelong jazz lover, preferring Miles Davis to Elvis Presley. But Keith Richards used the records of Muddy Waters and other Chicago blues icons to give the Stones their name and much of their sound – and to convert Watts into a rock and roll drummer.

The Rolling Stones, of course, have played in Chicago several dozen times. But their first visit to Chicago was not to play a concert, but to record at Chess Studios.

“They came here on their first tour of America and they recorded in Chess Studios. Chess Records was so seminal and so important to them that it was a dream come true when the first time they were in America they got to record at Chess,” said Ileen Gallagher, the curator of the touring “Exhibitionism” exhibit of Rolling Stones memorabilia that made a stop at Navy Pier in 2017.

“Chicago is the home of the blues and the Stones are a band because of the blues, so the fact that it’s here, it’s the way it should be,” said Chicago photographer Paul Natkin told WBBM Newsradio in a 2017 interview about the exhibit at Navy Pier.

Chess Records was founded by brothers Leonard and Phil Chess in 1950. It is renowned as the recording home of Father of Rock and Roll Chuck Berry – who commuted to Chicago from St. Louis to record all his best-known hits – as well as R&B pioneer Bo Diddley, and blues icons Little Walter, Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon, and of course, Muddy Waters.

The Rolling Stones held a session at Chess Studios in June 1964. In his memoir, “Life,” guitarist Richards wrote that the band recorded 14 tracks in two days. The recordings included Bobby Womack’s “It’s All Over Now” – which became a hit for the Stones – as well as some blues and Berry covers, and an instrumental blues jam honoring the Near South Side street address of the Chess Studios, “2120 South Michigan Avenue.

Richards also wrote that they encountered Muddy Waters on a ladder painting the ceiling at Chess. Seventeen years later in 1981, Waters would join them onstage at the old Checkerboard Lounge, at 423 E. 43rd St. in Bronzeville, for a concert that was memorialized on the album “Live at the Checkerboard Lounge.”

The Rolling Stones’ first Chicago show was at the Arie Crown Theater at McCormick Place in the fall of 1964, and they have played many dozens of shows since. They’ve played at long-gone venues such as the International Amphitheatre and the Chicago Stadium, and extant venues from Soldier Field to the United Center and what is now Guaranteed Rate Field – as well as the old Double Door in Wicker Park and the Aragon Ballroom in Uptown.

They most recently played to a sold-out crowd at Soldier Field in 2019. And as Lin Brehmer of WXRT radio recalled, Watts was as great as ever.

“And there was Charlie, what – 78 years old? Pounding the skins,” Brehmer said, “and he was phenomenal.”

Brehmer added: “One of the things that’s driving me crazy today is people saying, ‘Oh, what an underrated drummer.’ And if you paid any attention to the Rolling Stones, nobody underrated Charlie Watts.”

[chicago.cbslocal.com]

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

bye bye johnny

()

Date: August 25, 2021 21:07

Kenney Jones says Charlie Watts was Stones' 'secret ingredient'

Late Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts has been described as the band's "secret ingredient" by his friend, Faces rocker Kenney Jones.

BANG Showbiz

Kenney, 72, was grieving just like the rest of the rock community after hearing of Charlie's passing at the age of 80 on Tuesday (24.08.21) and he praised the 'Gimme Shelter' rocker for giving the group their "heartbeat".

Speaking exclusively to BANG Showbiz, Kenney said: "Charlie's playing with The Stones, he put a swing in their beat, just like I put a swing in our beat. It's the secret ingredient he had which was to provide those swing beats.

"He was the heartbeat of the band, their backbone.

"Also, Charlie never changed, that's one thing that I'm very proud of him for, he stuck to his guns and said, 'I'm only ever going to play me.' "

Kenney and Charlie were friends and toured together, along with a host of rock legends, for the ARMS Charity Concerts which took place in 1983 to raise money and awareness for Action into Research for Multiple Sclerosis, and he has nothing but fond memories of the time they spent together.

He remembered: "He wasn't outrageous, he wasn't a Keith Moon!

"Charlie was a nice guy. I knew him in the days when he was drinking and I knew him in the days when he gave up drinking, he was a gentleman all the way through. We would talk to each other about old times.

"We toured with each other a lot in '83 on the ARMS tour for multiple sclerosis with Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, Paul Rodgers, Joe Cocker and many others, we had a good time. We toured the States for about five weeks, we had a great time playing together, and in the bar."

Kenney also revealed that he called his Faces bandmate, and Rolling Stones guitarist, Ronnie Wood after hearing that Charlie had died to offer his condolences.

He shared: "I called him [Ronnie] immediately after I found out, he answered straight away, I said, 'I'm sorry.' We both knew it was going to happen, but Ronnie said, 'We knew it was going to happen but it doesn't matter how much you prepare for it, you're never prepared.'"

Ronnie, 74, has reunited with drummer Kenney and singer Sir Rod Stewart, 76, to record new Faces material.

[www.msn.com]

Late Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts has been described as the band's "secret ingredient" by his friend, Faces rocker Kenney Jones.

BANG Showbiz

Kenney, 72, was grieving just like the rest of the rock community after hearing of Charlie's passing at the age of 80 on Tuesday (24.08.21) and he praised the 'Gimme Shelter' rocker for giving the group their "heartbeat".

Speaking exclusively to BANG Showbiz, Kenney said: "Charlie's playing with The Stones, he put a swing in their beat, just like I put a swing in our beat. It's the secret ingredient he had which was to provide those swing beats.

"He was the heartbeat of the band, their backbone.

"Also, Charlie never changed, that's one thing that I'm very proud of him for, he stuck to his guns and said, 'I'm only ever going to play me.' "

Kenney and Charlie were friends and toured together, along with a host of rock legends, for the ARMS Charity Concerts which took place in 1983 to raise money and awareness for Action into Research for Multiple Sclerosis, and he has nothing but fond memories of the time they spent together.

He remembered: "He wasn't outrageous, he wasn't a Keith Moon!

"Charlie was a nice guy. I knew him in the days when he was drinking and I knew him in the days when he gave up drinking, he was a gentleman all the way through. We would talk to each other about old times.

"We toured with each other a lot in '83 on the ARMS tour for multiple sclerosis with Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, Paul Rodgers, Joe Cocker and many others, we had a good time. We toured the States for about five weeks, we had a great time playing together, and in the bar."

Kenney also revealed that he called his Faces bandmate, and Rolling Stones guitarist, Ronnie Wood after hearing that Charlie had died to offer his condolences.

He shared: "I called him [Ronnie] immediately after I found out, he answered straight away, I said, 'I'm sorry.' We both knew it was going to happen, but Ronnie said, 'We knew it was going to happen but it doesn't matter how much you prepare for it, you're never prepared.'"

Ronnie, 74, has reunited with drummer Kenney and singer Sir Rod Stewart, 76, to record new Faces material.

[www.msn.com]

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

JadedFaded

()

Date: August 25, 2021 21:10

Today is harder than yesterday. Today it’s real. Today the tears are flowing for this beloved man who brought us all such great musical joy.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

Hairball

()

Date: August 25, 2021 22:23

From the Rolling Stone article posted above:

"Keith Richards tells me, more than once, that Watts is essentially the reason that he still plays with Mick Jagger, and the reason the Rolling Stones endure so well and renew so effectively.

Jagger, too, has said he can’t imagine the band continuing without Watts. The Rolling Stones could survive the loss of guitarists Brian Jones and Mick Taylor, and the departure of bassist Bill Wyman.

They can withstand years of a world’s distance apart from one another. But they can’t imagine truly being the Rolling Stones without Charlie Watts.

Watts is similar-minded: “They are the only people I want to play rock & roll with.”'

We know Keith has said something along those lines on one occasion ( "no Charlie...no Stones" ), but does anyone know when Mick said something about this?

Still deeply saddened by this news...Charlie will be missed...damn....I was upset with the news about him missing the tour, but this........the magnitude of his passing is immense....

_____________________________________________________________

Rip this joint, gonna save your soul, round and round and round we go......

"Keith Richards tells me, more than once, that Watts is essentially the reason that he still plays with Mick Jagger, and the reason the Rolling Stones endure so well and renew so effectively.

Jagger, too, has said he can’t imagine the band continuing without Watts. The Rolling Stones could survive the loss of guitarists Brian Jones and Mick Taylor, and the departure of bassist Bill Wyman.

They can withstand years of a world’s distance apart from one another. But they can’t imagine truly being the Rolling Stones without Charlie Watts.

Watts is similar-minded: “They are the only people I want to play rock & roll with.”'

We know Keith has said something along those lines on one occasion ( "no Charlie...no Stones" ), but does anyone know when Mick said something about this?

Still deeply saddened by this news...Charlie will be missed...damn....I was upset with the news about him missing the tour, but this........the magnitude of his passing is immense....

_____________________________________________________________

Rip this joint, gonna save your soul, round and round and round we go......

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

CindyC

()

Date: August 25, 2021 22:36

Quote

JadedFaded

Today is harder than yesterday. Today it’s real. Today the tears are flowing for this beloved man who brought us all such great musical joy.

Agree, yesterday was the shock, and just re-reading the news. Today, dealing with the loss. It's a beautiful day here in Massachusetts, and I'm in a dark room by myself staring at a computer. If someone didn't bring me food yesterday, i wouldn't have eaten. I think it's hitting us all really hard. I am sending a virtual hug to everyone that is hurting over this.

Sorry, only registered users may post in this forum.

Online Users

Ali , Chastity , ChrisL , crholmstrom , erbissell , GeirGG , Irix , IsakSun , juano , Justjon , keef62 , Lil' Brian , NICOS , rastakeith , slewan , spidey39 , spunky , trm15 , TW2019 , werner67976

Guests:

2595

Record Number of Users:

206

on June 1, 2022 23:50

Record Number of Guests:

9627

on January 2, 2024 23:10