Tell Me :

Talk

When the US government has made its final decision. Otherwise see also the thread here - [iorr.org] .

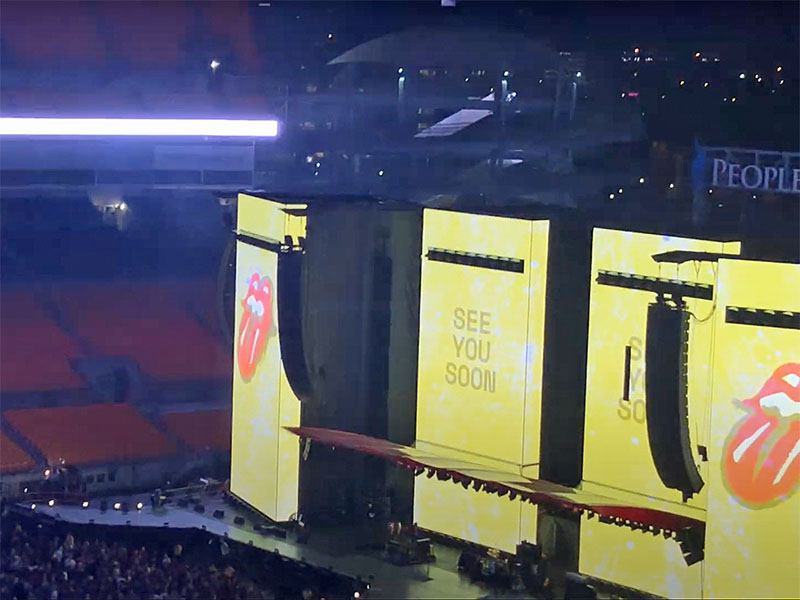

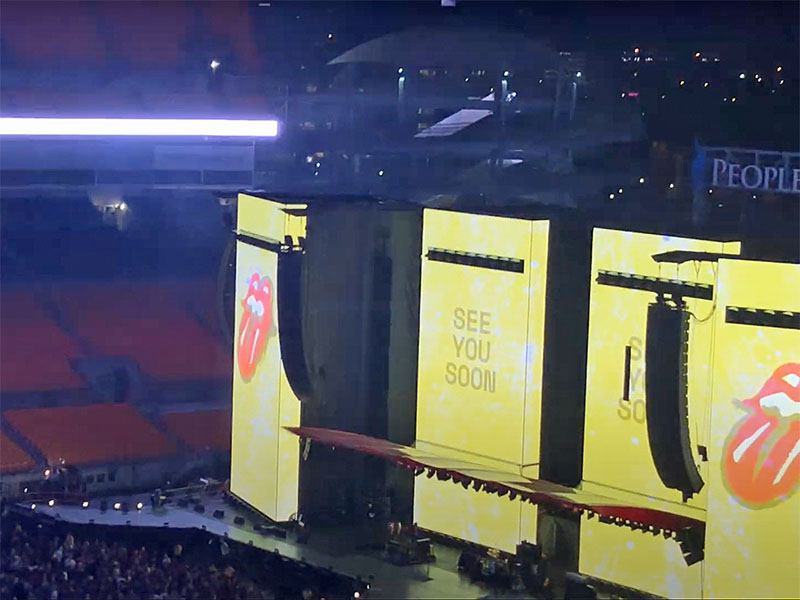

"See you soon":

Pittsburgh, 4-Oct-2021 - [www.YouTube.com] - (Pos. 2:10:05).

"soon" = at one of the next shows of the 2021 tour

Miami, 30-Aug-2019: "When Keith Richards spoke he said, 'this is our last show… for a bit' and the video screens at the end showed the message 'see you soon'." - [iorr.org] , [iorr.org] .

i.e. they have no clue. I was surprised to see this Stones reference a little further down.

The Independent travel correspondent Simon Calder said the White House’s lack of candour on when travel to the US can resume in earnest has been “extremely stressful for travellers, especially those who are desperate to seeloved ones the Rolling Stones in the US,” as well as for airline executives looking to maximise use of expensive aircraft and allocate resources such as fuel and personnel.

“Loved ones” and “The Rolling Stones” aren’t mutually exclusive, Mr. Goodman

Where did you see that? Reliable news or fake news?!

"U.S. Reportedly Opening Borders On 8 November To EU, U.K. Travelers" - [www.Forbes.com] .

"US set to lift UK travel ban on November 8 - Exclusive: Joe Biden is understood to be eyeing the early November date for restarting transatlantic travel" - [www.Telegraph.co.uk] .

"U.S. to lift travel ban on Nov. 8, allowing vaccinated international visitors into the country" - [www.CNBC.com] .

"US to ease travel restrictions for vaccinated foreign nationals from Nov 8" - [www.FT.com] .

Edited 3 time(s). Last edit at 2021-10-15 16:30 by Irix.

Talk about your favorite band.

For information about how to use this forum please check out forum help and policies.

Re: Fans travelling from anywhere in the world to see The Stones in USA 2021?

Posted by:

jhrock83

()

Date: October 4, 2021 16:16

Do you know when the US border will be Open for the french and european foreigner ?

They're talking about november but I can't know when exactly ?

Many Thanks

They're talking about november but I can't know when exactly ?

Many Thanks

Re: Fans travelling from anywhere in the world to see The Stones in USA 2021?

Posted by:

Irix

()

Date: October 4, 2021 16:30

Quote

jhrock83

Do you know when the US border will be Open for the french and european foreigner ?

When the US government has made its final decision. Otherwise see also the thread here - [iorr.org] .

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

harald2002

()

Date: October 5, 2021 22:47

Still no news:

Europan Travellers

Europan Travellers

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

adamw3405

()

Date: October 6, 2021 19:14

News from a Sunday Times special correspondent is that this is now looking unlikely for early November unfortunately. "November" is still likely but they have hit 'multiple speedbumps' in getting this sorted - all very depressing :-(.

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

Irix

()

Date: October 6, 2021 22:25

6-Oct-2021: "The BBC's North America editor Jon Sopel is reporting a source has told him it is 'increasingly unlikely' US-UK travel will open up again by early November. Transport Secretary Grant Shapps told the Commons at the time that the relaxation would happen from 'early November' - but it now appears it could be pushed later into the month." -- [News.Sky.com] , [Twitter.com] .

6-Oct-2021: "US looks likely to delay reopening to British travellers. 'I think a line will be crossed if this is not sorted by Thanksgiving on November 25' someone familiar with talks told The Telegraph. The slated November date for the the US reopening to British and European travellers was plunged into uncertainty on Wednesday, amid reports that discussions to end the travel ban had hit complications" - [www.Telegraph.co.uk] - (paywalled).

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2021-10-07 14:50 by Irix.

6-Oct-2021: "US looks likely to delay reopening to British travellers. 'I think a line will be crossed if this is not sorted by Thanksgiving on November 25' someone familiar with talks told The Telegraph. The slated November date for the the US reopening to British and European travellers was plunged into uncertainty on Wednesday, amid reports that discussions to end the travel ban had hit complications" - [www.Telegraph.co.uk] - (paywalled).

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2021-10-07 14:50 by Irix.

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

SomeTorontoGirl

()

Date: October 7, 2021 14:19

Get in line, Canada, the U.S. has bigger problems than its closed border

By Edward KeenanWashington Bureau Chief

Wed., Oct. 6, 2021

WASHINGTON — There’s really no news on the state of the COVID-19 restrictions on Canadians entering the U.S., which is only noteworthy in that people expected there to be a change by now and there hasn’t been.

What the heck is going on?

And as I wrote on Tuesday, one frustration for many — including dozens of members of the U.S. Congress — is that there hasn’t really been any reasonable explanation in over a year about the rationale for the current policy. Any Canadian can fly into the U.S., but most — other than those considered “essential” and those with visa status — are not allowed to cross at land borders. How does that make sense?

It certainly doesn’t to Grant Davidson, a Milton resident who went to a family funeral in the U.S. with his sons. They are dual citizens, but he is not.

“I put my stuff in their car, went to the airport and, two flights later, was in Midland, MI,” he wrote. “About an hour later, my sons drove in and I got my stuff out of their car. It cost me about $500 to fly when I could have gone with them in the car for free in the same amount of time.”

U.S. customs officials and the White House have not explained the logic nor the considerations that is preventing them from changing the policy.

Many experts, members of Congress from both political parties, people who work on border issues and advocates who lobby on them say they aren’t getting clear information, officially or unofficially. With that caveat, some will nonetheless share their impressions about what’s really driving this decision-making process and what might change it.

Three explanations, most probably overlapping, seem to reflect a consensus best guess of those I’ve spoken with:

1. Mexico: Throughout the pandemic, COVID-19 deaths per capita in Mexico have been three times higher than in Canada, and Mexico has at points relied on vaccines from Russia and China that are not approved in the U.S. Aside from that, the politics of the U.S. southern land border are always a lightning rod because of immigration and refugee fights that dominate American partisan politics when they flare up, as they have this year.

For reasons of both public health and political optics, reopening the land border to Mexicans now is a potentially explosive issue.

So why does that have anything to do with us? Because the current border policy applies to both Mexico and Canada. Biden’s administration is very reluctant to change that, at least in part because it does not want to be accused of racism for giving preferential treatment to Canadians over Mexicans.

2. Logistics: Americans are expected to implement new vaccine and testing requirements for international air travellers within a month, and it has long been expected that they might be linked to land border reopenings as well. But how to do that — which vaccines to accept or not, what would constitute adequate proof of vaccination, which tests and timelines would be acceptable — is not straightforward, and there is debate about how to “operationalize” such a policy.

Of course, Canada has those requirements in place for Americans, and it has functioned as close to seamlessly as you could hope. I’ve heard speculation that American border authorities are skeptical that Canada’s standards are effective — for instance, Canada accepts cards with drugstore employees’ notes scrawled on them as proof of vaccination, and test results are typically printed using a normal laser printer.

There’s also the issue of whether to accept vaccines approved in Canada but not the U.S., such as AstraZeneca — a decision further complicated if Biden hopes to have a uniform policy at the Mexican border, where even more vaccines that have been outright rejected by the U.S. are in use.

Many think these concerns might be resolved with new international air travel policies soon to be announced, which have been worked out with European and other travellers in mind, and should set a standard for acceptable vaccines, testing, and proof of them. Such airport standards might be applied at land crossings, too.

3. Distractions: The U.S. faces defaulting on its debts by the end of the month if Congress can’t break a logjam. President Joe Biden’s core domestic economic policy is at the centre of a bitter fight in his own party. And an inquiry into the Jan. 6 insurrection attempt goes on, while Americans work fight to reform or protect election procedures to ensure the integrity of their democracy.

As I’ve put it before, when several rooms of your house are on fire, you don’t spend much time thinking about inviting your friends over for dinner. Opening the Canadian border isn’t particularly controversial, but it’s not a front-of-mind issue for most Americans. One political veteran I spoke with recently said that these kind of issues need “a Manchin or Sinema” — a senator or block of members of Congress who will hold the rest of the government’s priorities hostage until they get their way. Right now, the Canadian border doesn’t have anyone like that.

Some thought the priority of the issue might change when Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer — likely the second most powerful Democrat in Washington after Biden — demanded action in July, but he’s been silent since. Schumer represents New York state, where the border closure is a real source of economic and cultural distress, and he is up for re-election in 2022. If he decided to prioritize it, it would likely jump to the top of Biden’s crowded to-do list, since Schumer is key to implementing the rest of Biden’s agenda. But because he’s so key to that agenda, he is also occupied with trying to manage all those house-on-fire issues.

[www.thestar.com]

Chatting with many Americans while in line in Pittsburgh - they weren’t aware of this, particularly the dichotomy, and were floored.

(Edit - typo)

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2021-10-07 21:09 by SomeTorontoGirl.

By Edward KeenanWashington Bureau Chief

Wed., Oct. 6, 2021

WASHINGTON — There’s really no news on the state of the COVID-19 restrictions on Canadians entering the U.S., which is only noteworthy in that people expected there to be a change by now and there hasn’t been.

What the heck is going on?

And as I wrote on Tuesday, one frustration for many — including dozens of members of the U.S. Congress — is that there hasn’t really been any reasonable explanation in over a year about the rationale for the current policy. Any Canadian can fly into the U.S., but most — other than those considered “essential” and those with visa status — are not allowed to cross at land borders. How does that make sense?

It certainly doesn’t to Grant Davidson, a Milton resident who went to a family funeral in the U.S. with his sons. They are dual citizens, but he is not.

“I put my stuff in their car, went to the airport and, two flights later, was in Midland, MI,” he wrote. “About an hour later, my sons drove in and I got my stuff out of their car. It cost me about $500 to fly when I could have gone with them in the car for free in the same amount of time.”

U.S. customs officials and the White House have not explained the logic nor the considerations that is preventing them from changing the policy.

Many experts, members of Congress from both political parties, people who work on border issues and advocates who lobby on them say they aren’t getting clear information, officially or unofficially. With that caveat, some will nonetheless share their impressions about what’s really driving this decision-making process and what might change it.

Three explanations, most probably overlapping, seem to reflect a consensus best guess of those I’ve spoken with:

1. Mexico: Throughout the pandemic, COVID-19 deaths per capita in Mexico have been three times higher than in Canada, and Mexico has at points relied on vaccines from Russia and China that are not approved in the U.S. Aside from that, the politics of the U.S. southern land border are always a lightning rod because of immigration and refugee fights that dominate American partisan politics when they flare up, as they have this year.

For reasons of both public health and political optics, reopening the land border to Mexicans now is a potentially explosive issue.

So why does that have anything to do with us? Because the current border policy applies to both Mexico and Canada. Biden’s administration is very reluctant to change that, at least in part because it does not want to be accused of racism for giving preferential treatment to Canadians over Mexicans.

2. Logistics: Americans are expected to implement new vaccine and testing requirements for international air travellers within a month, and it has long been expected that they might be linked to land border reopenings as well. But how to do that — which vaccines to accept or not, what would constitute adequate proof of vaccination, which tests and timelines would be acceptable — is not straightforward, and there is debate about how to “operationalize” such a policy.

Of course, Canada has those requirements in place for Americans, and it has functioned as close to seamlessly as you could hope. I’ve heard speculation that American border authorities are skeptical that Canada’s standards are effective — for instance, Canada accepts cards with drugstore employees’ notes scrawled on them as proof of vaccination, and test results are typically printed using a normal laser printer.

There’s also the issue of whether to accept vaccines approved in Canada but not the U.S., such as AstraZeneca — a decision further complicated if Biden hopes to have a uniform policy at the Mexican border, where even more vaccines that have been outright rejected by the U.S. are in use.

Many think these concerns might be resolved with new international air travel policies soon to be announced, which have been worked out with European and other travellers in mind, and should set a standard for acceptable vaccines, testing, and proof of them. Such airport standards might be applied at land crossings, too.

3. Distractions: The U.S. faces defaulting on its debts by the end of the month if Congress can’t break a logjam. President Joe Biden’s core domestic economic policy is at the centre of a bitter fight in his own party. And an inquiry into the Jan. 6 insurrection attempt goes on, while Americans work fight to reform or protect election procedures to ensure the integrity of their democracy.

As I’ve put it before, when several rooms of your house are on fire, you don’t spend much time thinking about inviting your friends over for dinner. Opening the Canadian border isn’t particularly controversial, but it’s not a front-of-mind issue for most Americans. One political veteran I spoke with recently said that these kind of issues need “a Manchin or Sinema” — a senator or block of members of Congress who will hold the rest of the government’s priorities hostage until they get their way. Right now, the Canadian border doesn’t have anyone like that.

Some thought the priority of the issue might change when Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer — likely the second most powerful Democrat in Washington after Biden — demanded action in July, but he’s been silent since. Schumer represents New York state, where the border closure is a real source of economic and cultural distress, and he is up for re-election in 2022. If he decided to prioritize it, it would likely jump to the top of Biden’s crowded to-do list, since Schumer is key to implementing the rest of Biden’s agenda. But because he’s so key to that agenda, he is also occupied with trying to manage all those house-on-fire issues.

[www.thestar.com]

Chatting with many Americans while in line in Pittsburgh - they weren’t aware of this, particularly the dichotomy, and were floored.

(Edit - typo)

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2021-10-07 21:09 by SomeTorontoGirl.

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

glimmertwinz

()

Date: October 7, 2021 19:41

Clowns!!!

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

hockenheim95

()

Date: October 11, 2021 19:12

It's getting really strange now. Early November is in just three weeks and still no word on a concrete Date...

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

Hairball

()

Date: October 11, 2021 19:22

One of the many reasons this tour is so strange...lots of people from different countries are unable to attend.

_____________________________________________________________

Rip this joint, gonna save your soul, round and round and round we go......

_____________________________________________________________

Rip this joint, gonna save your soul, round and round and round we go......

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

MisterDDDD

()

Date: October 11, 2021 19:43

Met a lot of people from other countries, surprisingly, at the opener in St Louis.

Hoping they announce it soon to afford many more to catch the last half of the tour! Would be great as early as the Vegas show.

Hoping they announce it soon to afford many more to catch the last half of the tour! Would be great as early as the Vegas show.

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

glimmertwinz

()

Date: October 12, 2021 13:04

Due to come to the Vegas gig but still no confirmation of date. Travelling from the UK. I did say to my wife that my real worry is that I would miss what very may well be the last US tour

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

adamw3405

()

Date: October 12, 2021 13:14

I'm in exactly the same boat - hoping to do Austin as well - everything crossed!

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

Irix

()

Date: October 12, 2021 13:25

Quote

glimmertwinz

I did say to my wife that my real worry is that I would miss what very may well be the last US tour

"See you soon":

Pittsburgh, 4-Oct-2021 - [www.YouTube.com] - (Pos. 2:10:05).

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

hockenheim95

()

Date: October 13, 2021 07:48

[www.nytimes.com]

Land Border to Canada and Mexico will be Open in November! This is increases the chance of Air traveling from Europe!

Land Border to Canada and Mexico will be Open in November! This is increases the chance of Air traveling from Europe!

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

mosthigh

()

Date: October 13, 2021 09:02

Yes, land border will be open towards the end of Stones tour. Probably be a few Canucks in Detroit.

[www.cbc.ca] (no paywall)

[www.cbc.ca] (no paywall)

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

adamw3405

()

Date: October 13, 2021 16:04

Announcement due today apparently!!! Keep everything crossed early November means EARLY November.....

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

angee

()

Date: October 13, 2021 16:11

Yes: Borders opened soon between US, Mexico and Canada!

Anyone from those countries want to come to any of the last four or five shows?

[www.cnn.com]

Still no exact date, just "early November."

~"Love is Strong"~

Anyone from those countries want to come to any of the last four or five shows?

[www.cnn.com]

Still no exact date, just "early November."

~"Love is Strong"~

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

slewan

()

Date: October 13, 2021 16:22

Quote

IrixQuote

glimmertwinz

I did say to my wife that my real worry is that I would miss what very may well be the last US tour

"See you soon":

Pittsburgh, 4-Oct-2021 - [www.YouTube.com] - (Pos. 2:10:05).

"soon" = at one of the next shows of the 2021 tour

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

Irix

()

Date: October 13, 2021 17:25

Quote

slewan

"soon" = at one of the next shows of the 2021 tour

Miami, 30-Aug-2019: "When Keith Richards spoke he said, 'this is our last show… for a bit' and the video screens at the end showed the message 'see you soon'." - [iorr.org] , [iorr.org] .

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

Irix

()

Date: October 14, 2021 19:00

14-Oct-2021: "'We said we’ll have this in coming days,' a White House official told The Independent in response to a query on when exactly America’s borders would reopen. Another suggested that the date would be sometime around the second week of November." - [www.Independent.co.uk] .

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

DeanGoodman

()

Date: October 14, 2021 19:11

Quote

Irix

14-Oct-2021: "'We said we’ll have this in coming days,' a White House official told The Independent in response to a query on when exactly America’s borders would reopen. Another suggested that the date would be sometime around the second week of November." - [www.Independent.co.uk] .

i.e. they have no clue. I was surprised to see this Stones reference a little further down.

The Independent travel correspondent Simon Calder said the White House’s lack of candour on when travel to the US can resume in earnest has been “extremely stressful for travellers, especially those who are desperate to see

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

BFR

()

Date: October 14, 2021 20:58

Quote

DeanGoodman

i.e. they have no clue. I was surprised to see this Stones reference a little further down.

The Independent travel correspondent Simon Calder said the White House’s lack of candour on when travel to the US can resume in earnest has been “extremely stressful for travellers, especially those who are desperate to seeloved onesthe Rolling Stones in the US,” as well as for airline executives looking to maximise use of expensive aircraft and allocate resources such as fuel and personnel.

“Loved ones” and “The Rolling Stones” aren’t mutually exclusive, Mr. Goodman

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

adamw3405

()

Date: October 15, 2021 15:38

Looks like the 8th from today's news.....damn - no Vegas then :-(

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

Manofwealthandtaste

()

Date: October 15, 2021 16:05

Quote

adamw3405

Looks like the 8th from today's news.....damn - no Vegas then :-(

Where did you see that? Reliable news or fake news?!

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

Irix

()

Date: October 15, 2021 16:18

Quote

Manofwealthandtaste

Where did you see that?

"U.S. Reportedly Opening Borders On 8 November To EU, U.K. Travelers" - [www.Forbes.com] .

"US set to lift UK travel ban on November 8 - Exclusive: Joe Biden is understood to be eyeing the early November date for restarting transatlantic travel" - [www.Telegraph.co.uk] .

"U.S. to lift travel ban on Nov. 8, allowing vaccinated international visitors into the country" - [www.CNBC.com] .

"US to ease travel restrictions for vaccinated foreign nationals from Nov 8" - [www.FT.com] .

Edited 3 time(s). Last edit at 2021-10-15 16:30 by Irix.

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

Manofwealthandtaste

()

Date: October 15, 2021 16:43

Thank you kindly, Irix

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

Manofwealthandtaste

()

Date: October 15, 2021 17:30

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

hockenheim95

()

Date: October 15, 2021 18:48

This topic should be sticky!!!

For many of us Europeans this is a great day! We just booked flights for November 8 and we will be attending at least three shows (Atlanta, Detroit, Austin) and hopefully we'll be able to get tickets for the Florida show! Really looking forward to jump on this tour! Better later than never :-) woohooo

For many of us Europeans this is a great day! We just booked flights for November 8 and we will be attending at least three shows (Atlanta, Detroit, Austin) and hopefully we'll be able to get tickets for the Florida show! Really looking forward to jump on this tour! Better later than never :-) woohooo

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

angee

()

Date: October 15, 2021 18:55

Ban is lifted across US borders on Nov. 8th.

Congrats, hockenheim 95.

~"Love is Strong"~

Congrats, hockenheim 95.

~"Love is Strong"~

Re: Travel international to USA fall 2021

Posted by:

eismann

()

Date: October 15, 2021 19:49

Yes! ATL I'm coming! See you there

the greatest rock and roll band in the world - definitely

the greatest rock and roll band in the world - definitely

Sorry, only registered users may post in this forum.

Online Users

Guests:

1146

Record Number of Users:

206

on June 1, 2022 23:50

Record Number of Guests:

9627

on January 2, 2024 23:10