For information about how to use this forum please check out forum help and policies.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

Lady Jayne

()

Date: August 26, 2021 19:50

Thank you to everyone who is posting links to tributes and photos. It is really helping to read so many appreciative words about Charlie.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

GivenToFly15

()

Date: August 26, 2021 19:52

The french newspaper Libération yesterday (wednesday)

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

DiegoGlimmerStones

()

Date: August 26, 2021 19:53

Rest In Peace dear Charlie, may god bless you, your family and your loved ones

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2021-08-26 20:04 by DiegoGlimmerStones.

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2021-08-26 20:04 by DiegoGlimmerStones.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

FrogSugar

()

Date: August 26, 2021 20:04

Quote

GivenToFly15

The french newspaper Libération yesterday (wednesday)

I browsed the article. Says he underwent "a serious heart operation" (the "medical procedure" term was a rather light way of putting it...).

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

Naturalust

()

Date: August 26, 2021 20:06

Quote

downagain

I've read a number of comments from people feeling a bit silly that they are so upset regarding the passing of someone they never met. Aside from saying that there's nothing wrong with feeling what you're feeling, I'll leave a quote I read when Bowie passed.

"We mourn our musical heroes not because we knew them but because they helped us know ourselves."

That is brilliant and timely and helpful beyond words. Thank you. Add we are all brothers and made from the same stardust so it applies to all humanity its pono brah! (Hawaiian def.) Aloha.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

Paddy

()

Date: August 26, 2021 20:31

video: [m.youtube.com]

Woke this morning with this in my head. Thanks again for all you put into the world Charlie.

Woke this morning with this in my head. Thanks again for all you put into the world Charlie.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

memphiscats

()

Date: August 26, 2021 20:39

Beautifully put. Thank you for sharing!Quote

NaturalustQuote

downagain

I've read a number of comments from people feeling a bit silly that they are so upset regarding the passing of someone they never met. Aside from saying that there's nothing wrong with feeling what you're feeling, I'll leave a quote I read when Bowie passed.

"We mourn our musical heroes not because we knew them but because they helped us know ourselves."

That is brilliant and timely and helpful beyond words. Thank you. Add we are all brothers and made from the same stardust so it applies to all humanity its pono brah! (Hawaiian def.) Aloha.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

swiss

()

Date: August 26, 2021 20:42

hey @MisterDDDD - hope you've been well  Your posts of tributes seem majorly appreciated for so many people here. I'll probbaly come back and visit them in the future, and for now because I'm processing the way I tend to, I literally can't take in any additional info yet except what fans here on IORR and friends otherwise are posting - as you say, "the show must go on" is a great way to approach it all too -- whatever works for people -- no 2 the same. Take care -swiss

Your posts of tributes seem majorly appreciated for so many people here. I'll probbaly come back and visit them in the future, and for now because I'm processing the way I tend to, I literally can't take in any additional info yet except what fans here on IORR and friends otherwise are posting - as you say, "the show must go on" is a great way to approach it all too -- whatever works for people -- no 2 the same. Take care -swiss

Your posts of tributes seem majorly appreciated for so many people here. I'll probbaly come back and visit them in the future, and for now because I'm processing the way I tend to, I literally can't take in any additional info yet except what fans here on IORR and friends otherwise are posting - as you say, "the show must go on" is a great way to approach it all too -- whatever works for people -- no 2 the same. Take care -swiss

Your posts of tributes seem majorly appreciated for so many people here. I'll probbaly come back and visit them in the future, and for now because I'm processing the way I tend to, I literally can't take in any additional info yet except what fans here on IORR and friends otherwise are posting - as you say, "the show must go on" is a great way to approach it all too -- whatever works for people -- no 2 the same. Take care -swissRe: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

gotdablouse

()

Date: August 26, 2021 21:19

Quote

FrogSugarQuote

GivenToFly15

The french newspaper Libération yesterday (wednesday)

I browsed the article. Says he underwent "a serious heart operation" (the "medical procedure" term was a rather light way of putting it...).

That's right, I just read the article and it goes into a bit more detail actually "une opération sérieuse du coeur, faisant suite à un méchant Covid", so a serious heart operation following a severe case of Covid. Hadn't read that anywhere before. It's strange Libé would be breaking the news and not the UK papers...

--------------

IORR Links : Essential Studio Outtakes CDs : Audio - History of Rarest Outtakes : Audio

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

bam

()

Date: August 26, 2021 21:43

I have no idea if the heart operation story is true, but there are several random websites that printed the claim:

[www.iheart.com]

[radaronline.com]

[www.mylondon.news]

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2021-08-26 22:13 by bam.

[www.iheart.com]

[radaronline.com]

[www.mylondon.news]

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2021-08-26 22:13 by bam.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

witterings

()

Date: August 26, 2021 21:44

The German / French television station Arte changes the entire evening program on Friday due to the death of Charlie Watts.

It`s nice to be here, .....

It`s nice to be here, .....

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

GivenToFly15

()

Date: August 26, 2021 22:14

ARTE will broadcast Crossfire Hurricane and then the Fonda 2005 tomorrow evening.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

Irix

()

Date: August 26, 2021 22:30

Crossfire Hurricane, 27-Aug-2021

Germany: [www.arte.tv] - 21:45

France: [www.arte.tv] - 22:25

Sticky Fingers Live at the Fonda Theatre, 27-Aug-2021

Germany (Video): [www.arte.tv] - 23:35

France (Video): [www.arte.tv] - 00:20

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2021-08-26 22:35 by Irix.

Germany: [www.arte.tv] - 21:45

France: [www.arte.tv] - 22:25

Sticky Fingers Live at the Fonda Theatre, 27-Aug-2021

Germany (Video): [www.arte.tv] - 23:35

France (Video): [www.arte.tv] - 00:20

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2021-08-26 22:35 by Irix.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

MisterDDDD

()

Date: August 26, 2021 22:33

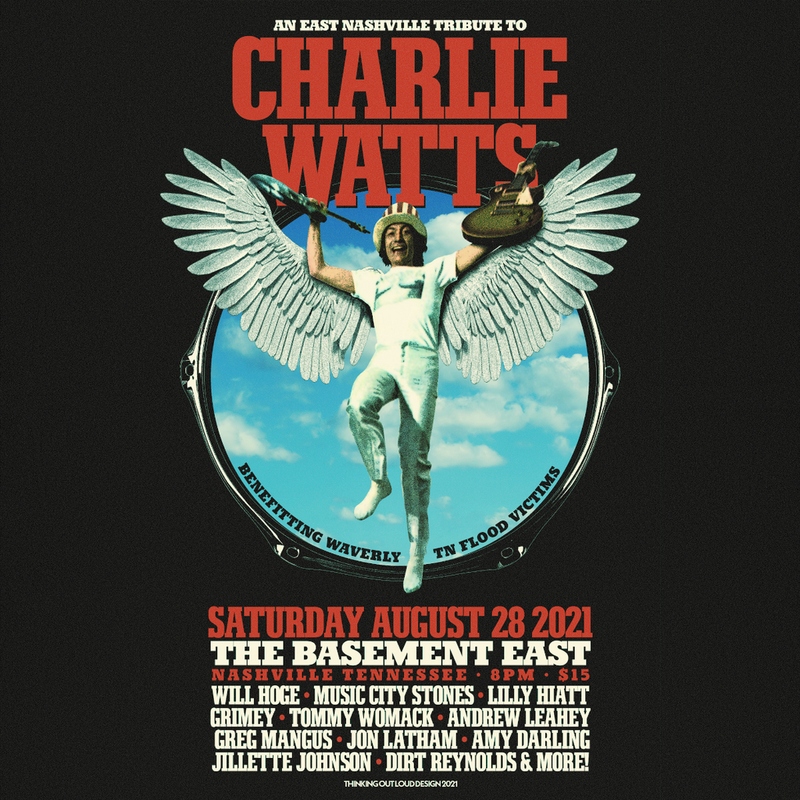

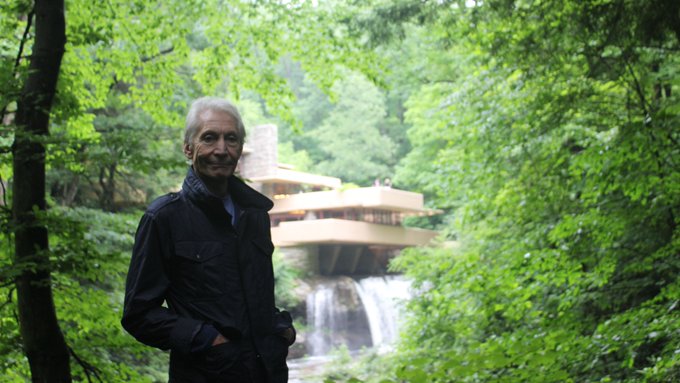

Great picture of Charlie at Falling Water.

Fallingwater:

Sharing this memory of Charlie Watts’ visit to Fallingwater in 2016 as Rolling Stones fans mourn his passing.

[twitter.com]

[fallingwater.org]

Fallingwater:

Sharing this memory of Charlie Watts’ visit to Fallingwater in 2016 as Rolling Stones fans mourn his passing.

[twitter.com]

[fallingwater.org]

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

MisterDDDD

()

Date: August 26, 2021 22:57

Good article here, apologies if already posted.

Swampers bassist David Hood remembers Charlie Watts, Rolling Stones’ Muscle Shoals sessions

[www.al.com]

Swampers bassist David Hood remembers Charlie Watts, Rolling Stones’ Muscle Shoals sessions

[www.al.com]

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

bye bye johnny

()

Date: August 26, 2021 22:57

Quote

gotdablouseQuote

FrogSugarQuote

GivenToFly15

The french newspaper Libération yesterday (wednesday)

I browsed the article. Says he underwent "a serious heart operation" (the "medical procedure" term was a rather light way of putting it...).

That's right, I just read the article and it goes into a bit more detail actually "une opération sérieuse du coeur, faisant suite à un méchant Covid", so a serious heart operation following a severe case of Covid. Hadn't read that anywhere before. It's strange Libé would be breaking the news and not the UK papers...

Link and full translation of article would be appreciated.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

Irix

()

Date: August 26, 2021 23:06

Quote

bye bye johnny

Link and full translation of article would be appreciated.

Liberation.fr , 25-Aug-2021 - [www.PressReader.com] :

Charlie Watts ne bat plus

Le batteur chic au swing et à la frappe subtile, le plus discret des Rolling Stones pendant cinquante-neuf ans, est mort mardi à Londres à l’âge de 80 ans.

Libération · 25 Aug 2021 · Par Olivier Lamm

Le batteur historique des Rolling Stones est mort mardi, à l’âge de 80 ans.

Il était à la fois une icône et un inconnu. Le fidèle, le muet, l’élégant Charlie Watts, indéfectible soutien rythmique et humain des Rolling Stones, dans le fond de la scène et des images depuis le premier jour – 1962 – n’est plus. Etrange événement que sa mort subite à 80 ans, d’ores et déjà traumatique, pour une histoire commune et ancienne, mais toujours pas révolue, qui n’en finit plus de déteindre sur notre présent éternellement nostalgique de ce qu’elle lui a laissé, celle du rock, et qui produit comme un bruit sourd : celui du son inimitable qu’il faisait tonner depuis les fûts comme de son attitude si étrangement débonnaire en toutes circonstances, au moment où ils s’échappent, et qui va à n’en pas douter provoquer un émoi international, et intergénérationnel. L’annonce, début août, de son absence de la énième tournée américaine des Stones qui devait débuter fin septembre à Saint-Louis (Missouri), pour des raisons de santé (une opération sérieuse du coeur, faisant suite à un méchant Covid), avait d’ailleurs ému, voire indigné – comment ça Watts, le «Silent Stone», ne serait pas là ? Et à quoi ressembleraient alors les concerts du groupe sans son swing, son ironie, sa frappe si subtile, et oui, sa douce, aimable récalcitrance ? C’est un fait, Charlie Watts, l’autre grand batteur de l’autre plus grand groupe de tous les temps, d’après la doxa, celui qui avait dit tant de fois n’être là que pour payer le loyer (personne ne le croyait à part les ennemis du groupe) était irremplaçable parce que d’ores et déjà dans l’histoire. Et l’histoire des Rolling Stones, sans lui, ressemble de moins en moins à celle d’un groupe dans l’action et de plus en plus à celle d’un groupe dans l’au-delà.

La collection d’un fanatique

Il était né Charles Robert Watts à Islington, Londres, le 2 juin 1951. Fils d’un chauffeur routier, doté d’un talent rare, l’ambidextrie, sa première passion musicale fut d’emblée, et sans la moindre ambiguïté, le jazz. Une passion qui ne le quitterait jamais, et qui lui fit se sentir ailleurs qu’à sa place, à différents degrés d’intensité, toute sa carrière au sein des Stones. A Serge Loupien, pour Libé en 1995, il évoquait sa découverte à 11 ans du Flamingo d’Earl Bostic, ancien sideman du grand Lionel Hampton, puis son coup de foudre pour Chico Hamilton. «J’ai alors acheté des disques de Louis Armstrong, de Johnny Dodds, de Duke Ellington et enfin de Charlie Parker… Je les possède toujours : Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Parker. Avec Buddy Rich à la batterie» – la collection d’un fanatique, d’un junkie dévorant une loupe sur le front les colonnes de Downbeat Magazine, pourtant plus souvent ému par les cuivres que par la batterie. Pourquoi se vouer alors à l’art du backbeat ? Par amour pour Joe Morello, batteur de Dave Brubeck, et par réalisme, le gamin Watts ne se sentant pas l’âme d’un virtuose, s’il faut se fier à ses dires. En 1955, ses parents lui dénichèrent, par le biais d’une petite annonce, sa première batterie miniature, une Viceroy, «idéale pour jouer dans les boums et jouer avec une radio ou un gramophone». Peu convaincu, il la pimpa en lui adjoignant le corps d’un banjo sans ses cordes, et se voua à imiter l’inimitable, Art Blakey. Suffisant pour se faire une place dans les groupes de skiffle du quartier, mais guère plus : le jeune Charlie s’en alla se lancer dans des études d’art. Devenu graphiste et grand lecteur de Kierkegaard et des Beats, c’est au Flamingo de Londres qu’il rêvait de faire ses armes, comme Ginger Baker, futur géant de Cream, ou son voisin le contrebassiste Dave Green. Mais c’est au sein du Blues Incorporated, formé par un certain Alexis Korner, que Watts, le disciple contraint de Charlie Parker, graphiste le jour pour faire rentrer les pounds (et rassurer papa et maman), allait débuter sa carrière de musicien. Devenu incontournable dans les clubs de rhythm’n’blues de la capitale britannique, c’est le plus naturellement du monde qu’il accepta de rejoindre, dans les derniers jours de 1962, un groupe à l’ambition déjà délirante, les Rolling Stones.

Dévoré tout cru

Que dire des cinquante-neuf années qui suivirent qui n’a pas déjà été raconté dans les biographies épaisses de Jagger et Richards, ses frères buvant bien mieux la lumière des spotlights, adeptes d’excès plus pittoresques (Watts fut alcoolique et junkie, mais plus mélancoliquement, en privé) et de natures plus tapageuses ? Que dire sinon que Watts, devenu Stone corps et âme, pilier, ne fut jamais aussi présent dans les Rolling Stones que sur la pochette de Between the Buttons, premier chef-d’oeuvre de son groupe dont il signa le graphisme, et sur laquelle il s’expose comme un leader paradoxal ? Que, dès 1965, il hurlait en silence sa frustration dans Ode To A High Flying Bird, un livre adorable sur la vie de Charlie Parker ? Qu’il était un mari fidèle qui refusa jusqu’au bout les avances de toutes les groupies? Ou encore que l’amène tragédie de sa vie fut que son jeu très jazz et très technique, permis par une poigne très souple comme seuls les jazzmen sont capables de la maîtriser, était mieux adapté à la musique révolutionnaire du méga groupe dont il était la star reconnaissable entre mille, qu’à ses propres explorations dans le domaine qui le passionnait? Avec Rocket 88, supergroupe de la jeune garde british, puis en quintet, ou en big-band, Watts enregistra beaucoup, sous son nom, des disques sans grand intérêt, moins pour la gloire que pour satisfaire des pulsions qui autrement, sur la route avec son mastodonte ou en studio pour en propulser à sa façon les tubes, l’auraient dévoré tout cru. Le deuxième batteur le plus célèbre du monde, c’est un fait, eut deux vies et aucune ne fut aussi satisfaisante que s’il avait pu les réunir en une seule. D’autres musiciens ont plus souffert, sans doute, et auront été plus malheureux.

A lire sur notre site, l’interview de Charlie Watts publiée en juin 1995.

A la question : «Si Charles Mingus ou Miles Davis vous avaient contacté, auriez-vous abandonné les Rolling Stones ?» Charlie Watts nous répondait: «J’aurais surtout eu un infarctus.»

Translation via DeepL.com:

Charlie Watts no longer beats

The chic drummer with the swing and subtle touch, the Rolling Stones' most discreet for fifty-nine years, died on Tuesday in London at the age of 80.

Libération · 25 Aug 2021 · By Olivier Lamm

The Rolling Stones' historic drummer died on Tuesday at the age of 80.

He was both an icon and an unknown. The faithful, the silent, the elegant Charlie Watts, unfailing rhythmic and human support of the Rolling Stones, in the background of the stage and the images since day one - 1962 - is no more. His sudden death at the age of 80 is a strange event, already traumatic for a common and ancient history, but still not over, which never ceases to rub off on our present, eternally nostalgic for what it has left, that of rock, and which produces a thud: That of the inimitable sound he made thundering from the drums as well as of his attitude so strangely debonair in all circumstances, at the moment when they escape, and which will undoubtedly provoke an international and intergenerational stir. The announcement, at the beginning of August, of his absence from the umpteenth American tour of the Stones, which was due to start at the end of September in St. Louis (Missouri), for health reasons (a serious heart operation, following a nasty Covid), had moreover moved, even indignant - what do you mean Watts, the "Silent Stone", wouldn't be there? And what would the band's concerts be like without his swing, his irony, his subtle touch, and yes, his gentle, kindly recalcitrance? It's a fact that Charlie Watts, the other great drummer of the other greatest band of all time, according to the doxa, the one who had said so many times that he was only there to pay the rent (nobody believed him except the band's enemies) was irreplaceable because he was already in history. And the Rolling Stones' story, without him, looks less and less like a band in action and more and more like a band in the afterlife.

The collection of a fanatic

He was born Charles Robert Watts in Islington, London, on 2 June 1951. The son of a lorry driver, gifted with the rare talent of ambidexterity, his first musical passion was, without the slightest ambiguity, jazz. A passion that would never leave him, and which made him feel out of place, to varying degrees of intensity, throughout his career with the Stones. To Serge Loupien, for Libé in 1995, he evoked his discovery at the age of 11 of Earl Bostic's Flamingo, a former sideman of the great Lionel Hampton, then his love affair with Chico Hamilton. "I then bought records of Louis Armstrong, Johnny Dodds, Duke Ellington and finally Charlie Parker... I still own them: Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Parker. With Buddy Rich on drums" - the collection of a fanatic, a junkie devouring the columns of Downbeat Magazine with a magnifying glass on his forehead, yet more often moved by brass instruments than by drums. So why devote himself to the art of the backbeat? Out of love for Joe Morello, Dave Brubeck's drummer, and out of realism, as the kid Watts didn't feel he had the soul of a virtuoso, if we are to believe his own words. In 1955, his parents found him his first miniature drum kit, a Viceroy, "ideal for playing at parties and playing with a radio or gramophone". Unconvinced, he gave it the body of a banjo without its strings, and devoted himself to imitating the inimitable Art Blakey. This was enough to earn him a place in the neighbourhood skiffle bands, but not much more: young Charlie went off to study art. He became a graphic designer and a great reader of Kierkegaard and the Beats, and it was at the Flamingo in London that he dreamed of making his mark, like Ginger Baker, the future giant of Cream, or his neighbour, the double bass player Dave Green. But it was within the Blues Incorporated, formed by a certain Alexis Korner, that Watts, the forced disciple of Charlie Parker, graphic designer by day to bring in the pounds (and reassure mum and dad), was to begin his musical career. Having become a fixture in the British capital's rhythm'n'blues clubs, it was only natural that he agreed to join the Rolling Stones, a band with already wild ambitions, in the last days of 1962.

Eaten alive

What can be said of the next fifty-nine years that has not already been told in the thick biographies of Jagger and Richards, his brothers much better at drinking the spotlight, adept at more picturesque excesses (Watts was an alcoholic and junkie, but more melancholy in private) and more boisterous natures? What can we say, except that Watts, who became Stone body and soul, a pillar, was never so present in the Rolling Stones as on the cover of Between the Buttons, his band's first masterpiece, for which he signed the artwork, and on which he is exposed as a paradoxical leader? That, as early as 1965, he was silently screaming his frustration in Ode To A High Flying Bird, a lovely book about Charlie Parker's life? That he was a faithful husband who refused the advances of all the groupies to the end? Or that the tragedy of his life was that his very jazz and technical playing, enabled by a very supple grip as only jazzmen can master it, was better suited to the revolutionary music of the mega band of which he was the recognisable star than to his own explorations in the field he was passionate about? With Rocket 88, a supergroup of the young British guard, and later as a quintet or big band, Watts made many records under his own name that were of little interest, less for the glory than to satisfy impulses that would otherwise have eaten him alive on the road with his behemoth or in the studio to propel the hits his way. The second most famous drummer in the world, it is a fact, had two lives and neither was as satisfying as if he had been able to combine them into one. Other musicians have suffered more, no doubt, and have been more unhappy.

Read the interview with Charlie Watts published in June 1995 on our website.

To the question: "If Charles Mingus or Miles Davis had contacted you, would you have left the Rolling Stones? Charlie Watts replied: "I would have had a heart attack."

Edited 2 time(s). Last edit at 2021-08-26 23:35 by Irix.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

SirCorto

()

Date: August 26, 2021 23:20

The most moving homage is the one of the official site. rollingstones.com.

Just a beautiful picture of Charlie and nothing else. Sometimes the simplest is the best. Just the picture and no links.

Just a beautiful picture of Charlie and nothing else. Sometimes the simplest is the best. Just the picture and no links.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

powerage78

()

Date: August 26, 2021 23:49

The sixtieth anniversary of the band will be without Charlie, and that too is so sad.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

bye bye johnny

()

Date: August 27, 2021 00:10

Thanks, lrix. That was a nice piece in Libération.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

Bastion

()

Date: August 27, 2021 00:14

Reading reports here on IORR of my last Stones show - Edinburgh 2018. This photo taken by Hendrik Mulder really got me.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

Sister Marie

()

Date: August 27, 2021 01:18

Hum, about the heart surgery I don't know, but about the Covid thing I wonder if it's not a leap due to a bad translation. Un raccourci, donc... Because on all the articles about this we can read the words about the heart surgery immediately followed by "After all the disappointment with delays to the tour caused by Covid, I really don’t want the many Stones fans in the States who have been holding tickets to have another postponement or cancellation." Just saying...

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

spiderman

()

Date: August 27, 2021 01:26

He was the coolest character, so down to earth. I'm really going to miss Charlie Watts. Thank you Charlie

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

shadooby

()

Date: August 27, 2021 01:36

Quote

Bastion

Reading reports here on IORR of my last Stones show - Edinburgh 2018. This photo taken by Hendrik Mulder really got me.

That is one of the most awesome pics I've ever seen of the Stones...and I've seen thousands. Thank you for that!

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

shadooby

()

Date: August 27, 2021 01:53

Voodoo Brew Disc 3...check it out.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

mmurphy0817

()

Date: August 27, 2021 01:55

First time poster- long time reader-

Like everyone it is hard to fathom Charlie's passing. We sort of thought of them all as lasting forever even though we know it's not possible or realistic, but the emotional side of all of us plays to this.

I have thought a lot about what they should do in terms of carrying on or calling it a day and since all of us process and handle grief differently I think we let them decide. If some of the reports are true that Charlie's passing was not a surprise but something that those close to the Stones knew was very inevitable in a very short amount of time then perhaps the issue was addressed by Charlie with Mick and Keith and Ronnie. Charlie's choosing of Steve Jordan may have been because he knew the end was very near and he wanted them to continue on. It doesn't mean that they are not devastated. All of us I am sure have been around family /friends who knew the end was near and when it finally came it was devastating. There is relatively little amount of emotional preparation that we can do even though we think we are doing it. Again it's that emotional grip that overcomes all of us.

My point is that, whatever they decide to do I will respect. People ask me what it is about them I love and my reply is always the same, 'the music touches my soul'.

Like everyone it is hard to fathom Charlie's passing. We sort of thought of them all as lasting forever even though we know it's not possible or realistic, but the emotional side of all of us plays to this.

I have thought a lot about what they should do in terms of carrying on or calling it a day and since all of us process and handle grief differently I think we let them decide. If some of the reports are true that Charlie's passing was not a surprise but something that those close to the Stones knew was very inevitable in a very short amount of time then perhaps the issue was addressed by Charlie with Mick and Keith and Ronnie. Charlie's choosing of Steve Jordan may have been because he knew the end was very near and he wanted them to continue on. It doesn't mean that they are not devastated. All of us I am sure have been around family /friends who knew the end was near and when it finally came it was devastating. There is relatively little amount of emotional preparation that we can do even though we think we are doing it. Again it's that emotional grip that overcomes all of us.

My point is that, whatever they decide to do I will respect. People ask me what it is about them I love and my reply is always the same, 'the music touches my soul'.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

kovach

()

Date: August 27, 2021 01:55

Quote

MizzAmandaJonez

Kovach is spot on with this idea:

“Maybe Mick or all 3 entering a dark stage and reading a short eulogy like Mick did for Brian at Hyde Park in 69 and starting the show off low-key with an acoustic melody of Salt of the Earth and Shine a Light or something before the standard video start to the main show. Maybe dedicate every show of this tour to Charlie. If they're going to carry on that might be the most fitting way.“

Loved the way The Eagles started a recent tour by strolling slowly out, playing a song from early in their career and then sitting down and telling a story to the audience.

Charlie deserves these shows to be all about him.

I also think this is it plus a few shows fir #60 as the final bows in a few select places or maybe just in London and NY?

It’s time.

You know, I think back 40 years to my first show, Charlie was the first one to walk out nonchalantly and take a seat behind the drums, the rest slowly walked out to the beginning drums of Under My Thumb...I was like, omg, I'm about to see the Rolling f*ckin Stones.

It's something I'll never forget even though I was barely 17 at the time.

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2021-08-27 02:02 by kovach.

Re: Charlie Watts Dies at 80

Posted by:

MAF

()

Date: August 27, 2021 02:04

Quote

Irix

Crossfire Hurricane, 27-Aug-2021

Germany: [www.arte.tv] - 21:45

France: [www.arte.tv] - 22:25

Sticky Fingers Live at the Fonda Theatre, 27-Aug-2021

Germany (Video): [www.arte.tv] - 23:35

France (Video): [www.arte.tv] - 00:20

Live At The Fonda Theatre

Rock And Roll Circus

Crossfire Hurricane

You can watch it whenever you want

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2021-08-27 02:08 by MAF.

Sorry, only registered users may post in this forum.

Online Users

Guests:

1271

Record Number of Users:

206

on June 1, 2022 23:50

Record Number of Guests:

9627

on January 2, 2024 23:10